Nigel Rawson | CHP | 15 November 2021

– Background –

The Patented Medicine Prices Review Board (PMPRB) is the federal tribunal whose role for the last 34 years has been to prevent time-limited patent monopolies for new medicines from charging “excessive” prices. In June 2016, it published a discussion document on proposed changes to its regulations, although the PMPRB leadership’s desire for revised regulations was apparent in their 2015-18 strategic plan.

Despite many criticisms to the planned changes from not only the biopharmaceutical industry but also patients, advocacy groups, physicians and other health professionals, the PMPRB and the federal government brushed them off and moved forward with the new rules. The implementation of the new regulations has been postponed three times – allegedly due to issues caused by the COVID-19 pandemic but more likely the result of evidence that the changes are ill-considered and broad-based stakeholder concern as well as several legal challenges – and is currently expected to occur in January 2022.

Throughout the past five years, the PMPRB and the federal government have maintained that the regulation changes will have little impact on the way the biopharmaceutical industry views Canada as a potential market for its products. They suggest that manufacturers will continue to perform research and development in Canada and to see Canada as a premier country in which to launch innovative drugs. This blinkered view ignores the fact that antagonistic policies in the form of rigid health technology assessments and non-transparent price negotiation processes have already reduced the industry’s interest in pursuing research, development and manufacturing in Canada. It also ignores data which have demonstrated that even the threat of the new regulations is deterring manufacturers’ interest in Canada.

– Previous Analyses –

In particular, the PMPRB has repeatedly suggested that the biopharmaceutical industry has not reduced its interest in performing research in Canada using data on newly approved clinical trials. However, the PMPRB’s analyses have failed to evaluate numbers of newly approved clinical trials by development phase.

Clinical trials of a new medicine in humans fall into three main phases designed to assess whether the medicine is safe, whether it works, and whether it is truly beneficial in real patients. Trials in the third phase are the most labour intensive and costly. They are also the most impactful on patients because they are testing medicines in patients (not healthy volunteers) with the condition for which the drug is indicated and, as such, are of direct interest to patients, particularly those with unmet health needs. Late-phase trials are commonly sponsored by manufacturers and, when performed in Canada, tend to indicate that the medicine will eventually be launched in this country. In contrast, trials sponsored by academic institutions are often earlier phase studies designed to answer esoteric scientific questions that are frequently of little direct interest or benefit to patients.

In February 2021, I demonstrated that the number of late development phase clinical trials of therapeutic and preventative medicines recorded in Health Canada’s publicly-available clinical trials database as being newly approved in the first half of each year between 2015 and 2019 was consistent (average: 135; range: 130 to 139). However, the number decreased in the first half of 2020 to 100 trials, 26% below the average over the preceding five years. A similar situation occurred in trials of oncology and non-oncology medicines, although the decrease was more apparent in non-oncology medicines. The reason for only analyzing new clinical trials approved in the first half of each year was the backlog of five to six months in the recording of trials in the database that had been previously identified by the PMPRB.

The PMPRB responded in a February 16 Twitter post suggesting that the number of late-phase trials approved in the second half of 2020 was consistent with the number in the first half. An implication of these results was that the backlog in recording trials had been eliminated in the month between the data extraction for my February 2021 article and the PMPRB’s Twitter post. However, unlike my work, the data reported by the PMPRB covered all late-phase trials regardless of whether sponsored by a biopharmaceutical company or an academic institution and, thus, failed to provide insight into any changes in the number of manufacturer-sponsored trials.

Since the recording backlog had been eliminated, I repeated my analysis using data from Health Canada’s database for each whole year between 2015 and 2020 in March 2021. Only a modest decrease of 7% occurred in the overall number of manufacturer-sponsored trials. However, between 2015 and 2020, the number of late-phase trials decreased by 23% (the decreases in oncology and non-oncology medicine trials were 15% and 25%, respectively).

Trials of COVID-19 therapies and vaccines increased the numbers in 2020. When these trials were excluded, the decrease in all manufacturer-sponsored trials between 2015 and 2020 was 12% and the reduction in late-phase trials of non-oncology medicines was 31%.

– PMPRB Latest Data –

At the 2021 Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) symposium, the PMPRB presented a poster about pharmaceutical research and development investment and the number of clinical trials in Canada. This included a figure of the total number of clinical trials approved in each half year between January 2016 and June 2021 and the percentage that were manufacturer-sponsored in each time period. With these data, the PMPRB claimed that, despite a steep reduction in the number of newly approved clinical trials in the first half of 2020, the number in the second half of the year “recovered to average levels.” The implication the PMPRB wants to convey is that the threat of the new regulations is not causing a decrease in the number of new clinical trials approved in Canada.

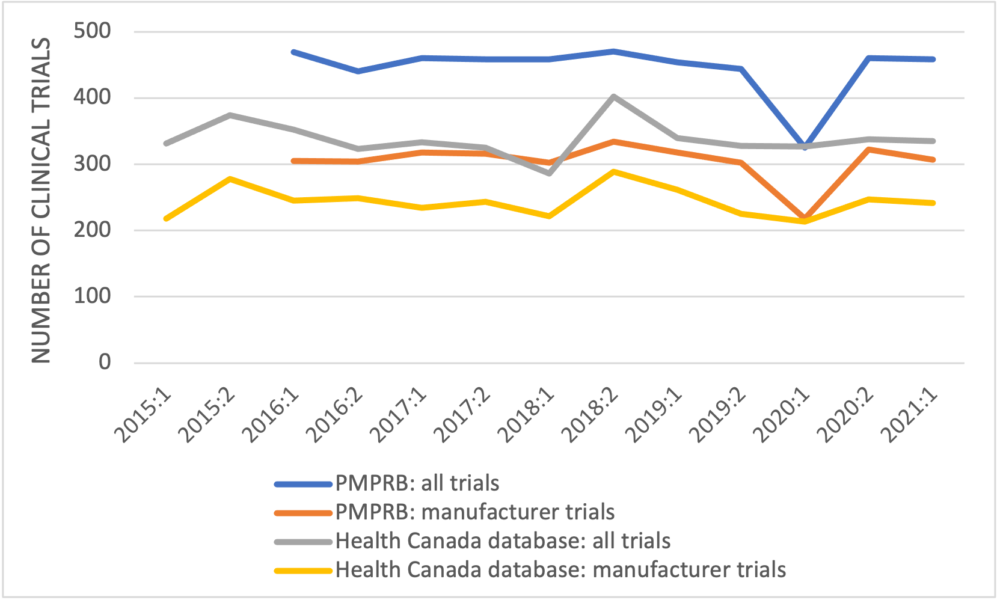

The first point to observe in the PMPRB’s data is that the numbers of newly approved clinical trials reported are larger than the numbers recorded in the publicly-available Health Canada database for every half-year but one (Figure 1). Where these data originate is not defined; they don’t come from the first two references provided in the PMPRB’s poster but likely come from the third reference, GlobalData, a data analytics company based in the United Kingdom.

Figure 1: Newly approved clinical trials reported by the PMPRB and Health Canada by half-year

The second point is that the number of clinical trials in 2015, which is higher than the numbers in most of the later years, is excluded. Finally, the PMPRB again fails to unpack its data to examine trends in the clinical trials by development phase.

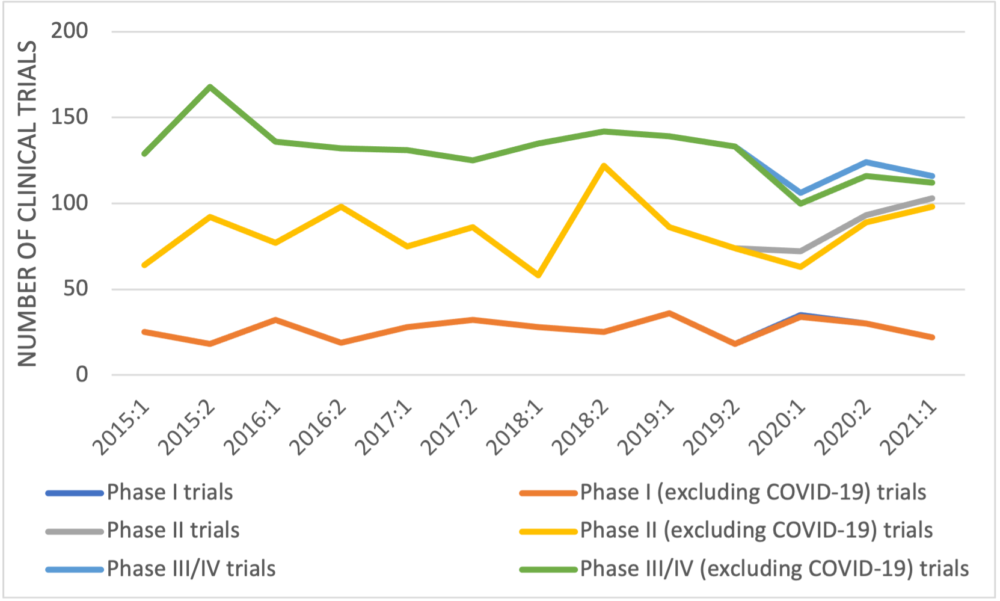

When manufacturer-sponsored trials recorded in Health Canada’s database are categorized by trial development phase (Figure 2), no trend is apparent in early-phase trials but the number of late-phase trials decreased from 168 in the second half of 2015 to 116 in the first half of 2021 – a reduction of 31%, 33% if COVID-19 late-phase trials are excluded. A similar trend was seen in the trials of non-oncology medicines with a reduction of 37% in the number of manufacturer-sponsored late-phase trials between 2015 and 2021 (45% if COVID-19 trials are excluded).

Figure 2: Newly approved clinical trials reported by Health Canada by half year and development phase

– Conclusion –

The PMPRB has used data from Health Canada’s clinical trials database in previous analyses. The data used in its CADTH symposium poster are inconsistent with information from Health Canada’s database. The PMPRB has also used GlobalData previously to suggest that not all approved clinical trials in Canada are recorded by Health Canada, although by 2019 the numbers of trials in Health Canada’s database were reasonably close to the number according to GlobalData. The question arises as to why Health Canada, the regulatory authority responsible for approving clinical trials, is not aware of all clinical trials in this country.

Whichever data source the PMPRB uses, it should provide a detailed analysis categorizing newly approved trials by sponsor type and development phase and accounting for other factors such as COVID-19 research. Simply providing overall data on newly approved trials seems designed to further the PMPRB’s misleading narrative that manufacturers are not responding negatively to its planned regulation revisions.

Information obtained from Health Canada’s publicly available database demonstrates that the PMPRB’s claim that the number of newly approved clinical trials has “recovered to average levels” is untrue with regard to manufacturer-sponsored trials. Late-phase manufacturer-sponsored trials are the costliest and the most labour intensive. They are also the ones most impactful on patients because they are testing medicines in patients with the condition for which the drug is indicated, medicines have undergone many safety assessments by this stage, and performing a late-phase trial in Canada frequently suggests that the developer will eventually launch the medicine in this country. A reduction in such trials is an indicator that the attractiveness of Canada as a country in which to launch new medicines has decreased.