Nigel Rawson and Brett Skinner | Hill Times | 7 SEP 2022

Uncertainty about PMPRB price regulations will deter new drug launches in Canada

Nigel Rawson and Brett Skinner

In April, the federal minister of health announced that the government would not proceed with two of three major pieces in its new regulatory guidelines for the Patented Medicine Prices Review Board (PMPRB) after successive court rulings quashed changes that would have introduced complex “pharmaco-economic” calculations and required drug companies to disclose confidentially negotiated rebates.

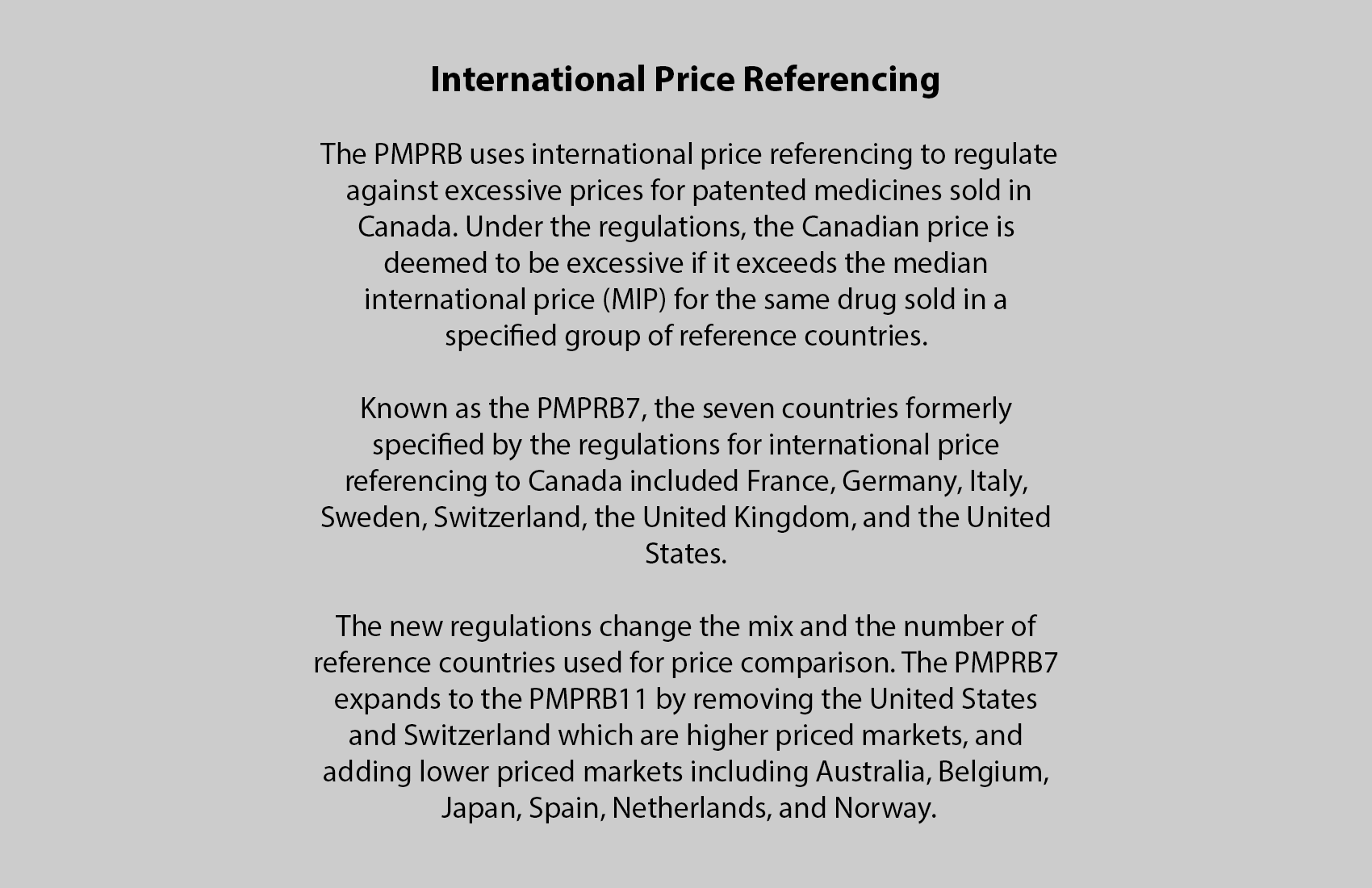

On July 1st, the government implemented the one surviving amendment which involved changing the group of reference countries used to set price ceilings for innovative medicines in Canada from seven to 11 by removing two countries with high drug prices and adding six with lower prices.

A recently published paper examined how this change will impact access to new drugs in Canada. Researchers considered the perspective of a global pharmaceutical executive in Europe or the United States deciding whether it’s sensible from a business perspective to launch an innovative medicine in Canada in the next 12 to 18 months. The analysis was based on a hypothetical rare disease medicine, which would have satisfied the PMPRB’s criteria for being classified as a breakthrough drug because it was “the first one sold in Canada that treats effectively a particular illness or addresses effectively a particular indication.” Under the PMPRB regulations, the maximum list price allowed for a breakthrough drug is the median of list prices in the reference countries. The case study showed how a drug’s list price could be less than the median of the list prices in the seven former countries used in the reference test when first sold in Canada and, therefore, PMPRB-compliant. However, the same list price would exceed the median of prices in the new set of 11 reference countries by at least 12.8%, which would require an equivalent price cut.

A recently published paper examined how this change will impact access to new drugs in Canada. Researchers considered the perspective of a global pharmaceutical executive in Europe or the United States deciding whether it’s sensible from a business perspective to launch an innovative medicine in Canada in the next 12 to 18 months. The analysis was based on a hypothetical rare disease medicine, which would have satisfied the PMPRB’s criteria for being classified as a breakthrough drug because it was “the first one sold in Canada that treats effectively a particular illness or addresses effectively a particular indication.” Under the PMPRB regulations, the maximum list price allowed for a breakthrough drug is the median of list prices in the reference countries. The case study showed how a drug’s list price could be less than the median of the list prices in the seven former countries used in the reference test when first sold in Canada and, therefore, PMPRB-compliant. However, the same list price would exceed the median of prices in the new set of 11 reference countries by at least 12.8%, which would require an equivalent price cut.

This may not seem a large percentage, but it could be sufficient to deter a manufacturer from launching a new medicine in Canada. When considering whether to launch a new medicine on Canada, pharmaceutical executives face a set of complex and difficult questions. Two fundamental ones are: will the PMPRB use its external reference pricing test with the new countries in the same way as it has in the past (the PMPRB has significant latitude in creating its new guidelines), and will the company’s target list price be PMPRB-compliant under the new rules?

Another issue for global executives to consider is whether the changes in Canada will impact their company’s business in other countries, especially those that use Canada as a comparator in their own reference pricing tests. Several of these countries have much larger populations than Canada and, consequently, are important potential markets for new medicines that manufacturers will not want jeopardized.

If executives are considering the launch of a rare disorder drug, they will have to take account of the likelihood that prices of these medicines will be particularly reined in under the new rules. The cancellation of most of the proposed PMPRB revisions does not mean that the federal government has abandoned its objective of reducing medicine prices in Canada.

With so much unknown, pharmaceutical executives’ decisions seem highly likely to be wait-and-see. If companies commonly make this decision, launches of new medicines in Canada will, at best, be delayed and, at worst, not happen.

Canada’s attractiveness as a marketplace for new medicines has already diminished as a result of uncertainty about the PMPRB changes; the uncertainty will persist while new guidelines are drafted. Further delays in access or complete denials of access to innovative drugs will hurt even more Canadians with unmet or poorly met health needs that could be helped by these medicines.

Nigel Rawson is an affiliate scholar with the Canadian Health Policy Institute and a Senior Fellow with the Macdonald-Laurier Institute. Brett Skinner is CEO of the Canadian Health Policy Institute.

A version of this article appeared in the Hill Times.