A Dollar a Day May Keep the Doctor Away: Putting Spending on Food and Healthcare on a Scale

Katerina Maximova PhD, MAP Centre for Urban Health Solutions, Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute, St. Michael’s Hospital; Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of Toronto, Toronto

Shelby Marozoff MSc, School of Public Health, University of Alberta, Edmonton

Arto Ohinmaa PhD, School of Public Health, University of Alberta, Edmonton

Paul J Veugelers PhD, School of Public Health, University of Alberta, Edmonton

ABSTRACT: In Canada, the economic burden from chronic diseases on healthcare systems is escalating and has the potential to significantly disrupt healthcare delivery in the years ahead. Unhealthy diet is a key preventable risk factor for chronic, non-communicable diseases, and, of all modifiable risk factors, has the largest impact on the global burden of chronic disease. Adherence to dietary recommendations is poor among Canadians, and the costs of healthful foods are often cited as an impediment to healthful dietary choices. But what does it cost us in terms of increased healthcare burden if we do not eat healthy? Canadians currently spend $9.34 per person per day on food, of which one dollar (10.7%) should be set aside for future use by the government for the treatment and management of chronic diseases because Canadians do not follow established dietary recommendations for healthy eating. In this commentary, we contend that relatively modest investments in dietary interventions to improve the affordability of healthful foods, to reduce the affordability of harmful foods, and to limit access and discourage consumption of inessential foods may have a significant impact on the chronic disease burden and help dramatically reduce the healthcare costs in Canada.

SUBMITTED: October 7, 2021 | PUBLISHED: February 23, 2022

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS: This work was funded through the Collaborative Research and Innovation Opportunities (CRIO) Team program from Alberta Innovates-Health Solutions awarded to PJV and AO (grant number: 201300671). SM received a stipend through this CRIO program.

DISCLOSURE: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

CONTRIBUTIONS: KM interpreted the data, drafted and revised the text, SM extracted relevant data, created the figure and assisted with drafting the text, AO conceived the methodology and guided data extraction and interpretation, PV conceived the idea, interpreted the data, and drafted and revised the text. All of the authors approved the final version to be published.

DISCLAIMER: Research conclusions and policy recommendations are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as a reflection of the opinions or policy positions of their employers and affiliated organizations.

CITATION: Maximova, Katerina et al (2022). A Dollar a Day May Keep the Doctor Away: Putting Spending on Food and Healthcare on a Scale. Canadian Health Policy, FEB 2022. ISSN 2562-9492 https://doi.org/10.54194/TUFN5875 www.canadianhealthpolicy.com.

Background

The treatment and management of chronic diseases accounts for the majority (67%) of direct healthcare costs in Canada, and the economic burden from these conditions on healthcare systems is enormous, costing $125 billion annually in direct costs alone (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2019). Due to the ageing population structure, longer life expectancy, and advances in treatment and management, the incidence and prevalence of chronic diseases and its economic burden will continue to escalate. A large proportion of these chronic diseases can be prevented or postponed through improvements in the four common behavioural risk factors: tobacco use, unhealthy diet, physical inactivity, and harmful use of alcohol (World Health Organization, 2013). Of these four factors, the 2017 Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study revealed that unhealthy diet was responsible for the largest burden of disease and the most deaths globally, particularly in high-income countries (GBD 2017 Diet Collaborators, 2019). The same GBD study reported that diets low in fruit, high in sodium, low in nuts and seeds, low in vegetables, and low in whole grains emerged as the leading risk factors, accounting for more than 50% of diet-related deaths and 66% of disability-adjusted life years. Additionally, high intakes of processed meat, trans fats and sugar-sweetened beverages were driving the burden in high-income North American countries (GBD 2017 Diet Collaborators, 2019).

To prevent chronic diseases, the recently released Canada’s Food Guide recommends a diet rich in vegetables and fruit, whole grains and plant-based protein foods (legumes, nuts and seeds), low on highly processed foods that contain added sodium, sugars or saturated fat, and replacing sugary drinks with water (Health Canada, 2019). In Canada, compliance with dietary recommendations is poor and shows little sign of improvement (Lieffers, Ekwaru, Ohinmaa, & Veugelers, 2018; Tugault-Lafleur & Black, 2019). Relative to 2004, Canadians in 2015 reported consuming fewer servings of vegetables and fruit, and of milk and alternatives along with only modest improvements in terms of increases in the consumption of plant-based foods (legumes, and nuts and seeds) and reductions in the consumption of high-calorie beverages (Tugault-Lafleur & Black, 2019).

Clearly, population-based interventions are sorely needed over and above the current efforts to reduce the consumption of unhealthy components (sodium, sugar, and fat) and to encourage the consumption of healthful foods (vegetables and fruit, nuts and seeds, and whole grains). The path forward and the economics of further investments in healthy eating are not clear. Do we actually know how much Canadians pay for food and for a healthy diet? And do we know how much Canadians pay for the healthcare burden caused by our unhealthy eating practices?

Analysis

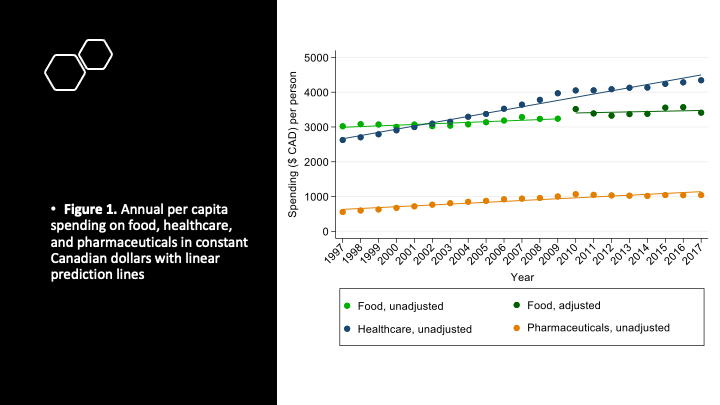

From publicly available data sources we compiled per capita expenditures on diet, healthcare, and pharmaceuticals in Canada over a 20-year period (Figure 1). Specifically, the expenditures for diet are out of pocket (Statistics Canada, 2010, 2021), whereas those for healthcare and pharmaceuticals are from both the publicly-funded healthcare system and the private sector (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2019), with per capita spending on pharmaceuticals by households or individuals paying out of pocket similar to that by the public sector (i.e., provincial/territorial programs, federal direct drug subsidy programs, and social security funds) and private sector (i.e., private health insurance): $354, $388, $333, respectively (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2018). Healthcare expenditures include hospitals and residential care facilities, physicians, and allied health professionals, and those for pharmaceuticals include prescribed and non-prescribed drugs.

Figure 1 illustrates that the actual amount of money spent by Canadians on food, either on groceries or at restaurants, has gradually increased over time, reaching in 2017 a per capita spending of $3,410 per year, equivalent to $9.34 daily, after inflation adjustment. Figure 1 also illustrates that healthcare expenditures have risen considerably over the past 20 years. Considering adjustment for inflation, per capita healthcare spending increased by 65.5% between 1997 and 2017, reaching $4,343 per year, or $11.90 daily, in 2017. With treatment and management of chronic diseases accounting for 67% of direct healthcare costs in Canada, this would entail the direct costs of chronic diseases to be $2,910 per capita, equivalent to $7.97 daily, in 2017. Similarly, per capita spending on pharmaceuticals increased by 87.6% between 1997 and 2017, and reached $1,042 per year, or $2.85 daily, in 2017 (Figure 1).

The economic burden of chronic diseases attributable to unhealthy eating, including both direct and indirect healthcare costs, was estimated at $13.8 billion in Canada in 2014 (Lieffers et al., 2018) and at $15.8 billion in 2018 (Loewen, Ekwaru, Ohinmmaa, & Veugelers, 2019). These estimates were based on not meeting the recommendations for five healthful foods (fruit, vegetables, whole grains, nuts and seeds, and milk) and for three harmful foods (processed meat, red meat, and sugar-sweetened beverages) (Lieffers et al., 2018). With a Canadian population of 35.5 million in 2014 (Statistics Canada, 2014), $13.8 billion translates into spending of $388 per capita per year or just over $1 per capita per day. This one dollar represents the costs that could have been avoided if Canadians had complied with established dietary recommendations. The one dollar is a cost to society because we have a public healthcare system. Where we had estimated the per capita daily costs for food to consumers to be $9.34, the per capita daily costs for food to society is $9.34 plus one dollar. This additional one dollar is the estimated value of the money that governments should set aside for future expenses for the treatment and management of diet-related chronic diseases that come ‘after the meal’.

Discussion

We, as a society, could decide to spend this dollar ‘before the meal’. We, as a society, could decide to invest this one dollar in healthy eating and herewith avoid the chronic diseases and associated healthcare costs that would have come ‘after the meal’. This one dollar currently amounts to approximately 10% of the per capita daily societal costs of food. Figure 1 shows that healthcare spending (and those of pharmaceuticals) increases at a faster rate than the costs for food (Figure 1). Driven by the projected increases in the chronic disease burden and the ageing population (GBD 2015 Risk Factors Collaborators, 2016), the share of chronic diseases in the overall disease burden is growing over time (World Health Organization, 2020) and has the potential to significantly disrupt the healthcare spending in the years ahead if measures to improve the diet of Canadians are not taken. Lieffers et al. (2018) further demonstrated a substantial ($4.9 billion per year) reduction in the economic burden if Canadians who are not meeting the dietary recommendations would consume half a serving more of the healthful foods and half a serving to one serving less of the harmful foods. In other words, facilitating relatively modest changes in diet can result in substantial reductions in the economic burden.

Looking back, one may speculate that if Canada had made more investments in the promotion of healthy eating in prior decades, enabling Canadians to achieve the above-mentioned modest improvements in diet, the healthcare expenditures for chronic diseases would be lower today. Looking forward, investing now in a healthier diet may have the potential to increase the spending on food but will come with the benefit of reduced healthcare expenditures in the years ahead.

Previous research has demonstrated that healthy diets are more expensive compared to unhealthy diets, that higher food prices disproportionately affect the diet quality of lower-income households, and that perceived and actual high cost of vegetables and fruit are key barriers to adopting a healthy diet (Darmon & Drewnowski, 2015). The prevailing view is that Canadians are not consuming enough healthful foods and that increasing their consumption of healthful foods would increase out of pocket expenditures on food. This view, however, ignores two other cost drivers. A reduction in the consumption of harmful foods will drive down the costs of an individual’s diet. However, Lieffers et al. (2018) and Loewen et al. (2019) both calculated the balance such that 77% to 79% of the healthcare costs attributable to diet can be avoided by eating more healthful foods, and that 21% to 23% can be avoided by eating less harmful foods. In relative terms therefore, expenditures on food would still go up when choosing a healthier diet.

Whereas there is extensive evidence on the health effects of the above mentioned healthful and harmful foods (GBD 2015 Risk Factors Collaborators, 2016), there is less evidence for another overlooked cost driver: inessential foods. Inessential foods include pastries, desserts, snack foods such as potato chips, candy bars, and sweets, among others and are typically high in calories and low in nutrients, and yet take up a substantial portion of Canadians’ diets. Bukambu et al. (2020) estimated the costs of inessential foods in the diets of Canadian children to be $1.39 per day. This amount is of similar magnitude as the difference in the costs of a diet of good quality and a diet of poor quality (Bukambu et al., 2020). This implies that health promotion and policy initiatives that enable consumers to reduce inessential foods would improve diet quality, and the money not spent on these inessential foods would create the financial space to purchase more healthful foods.

The rising costs of healthcare and pharmaceuticals are common features of political debate in Canada. However, the argument that a healthy diet prevents chronic diseases and herewith reduces healthcare costs is rarely mentioned. Likewise, the extent to which the mounting costs for the treatment of COVID-19 patients could have been alleviated if we had been more successful in promoting healthy eating and preventing obesity, type 2 diabetes, hypertension along with other underlying chronic conditions, is yet to be exposed. Evidence-based interventions to support population-level dietary improvements, including product reformulation, legislation to ban harmful foods, taxation, food pricing and economic incentives, food labelling and consumer information, restricted marketing to children, and the provision of healthful foods in schools, workplaces and other public institutions (World Health Organization, 2017), have comparatively low cost (less than one dollar per person annually) (World Health Organization, 2011). Investment in these interventions could pay for itself, in terms of future reductions of healthcare costs, via the $1 per day set aside for future use by the government for the treatment and management of chronic diseases, and, where needed, supplemented with revenue from the taxation of harmful foods. These funds could also be reinvested in the production, distribution, marketing of healthful foods to support improvements in nutritional quality of diets among the food insecure or low-income groups (Men et al, 2021; Kirkpatrick & Tarasuk, 2003), to help reduce their disproportionately higher chronic disease burden (World Health Organization, 2018). Low-income households not only have lower total food expenditures but also purchase fewer servings of vegetables and fruit (Kirkpatrick & Tarasuk, 2003). Population-level initiatives that promote the affordability of healthful foods, reduce the affordability of harmful foods, and limit access and discourage consumption of inessential foods constitute vital opportunities to reduce the chronic disease burden and its associated healthcare costs: The symbolic, earmarked value of $1 per day may well be enough to keep the doctor away.

References

Bukambu, E., Lieffers, J. R. L., Ekwaru, J. P., Veugelers, P. J., & Ohinmaa, A. (2020). The association between the cost and quality of diets of children in Canada. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 111(2), 269–277. https://doi.org/10.17269/s41997-019-00264-7

Canadian Health Policy Institute. (2021). Patented Medicines Expenditure in Canada 1990-2019. CHPI Annual Research Series. Canadian Health Policy. ISSN 2562-9492. www.canadianhealthpolicy.com

Canadian Institute for Health Information. (2019). National Health Expenditure Trends, 1975 to 2019. Series A: Summary data, Canada. Table A.3.1.3 Total health expenditure per capita by use of funds, in current dollars, Canada, 1975 to 2019. https://www.cihi.ca/en/national-health-expenditure-trends-1975-to-2019

Canadian Institute for Health Information. (2018). Information Sheet: Drug Spending at a Glance. How much do Canadians spend on drugs? https://www.cihi.ca/sites/default/files/document/nhex-drug-infosheet-2018-en-web.pdf

Darmon, N., & Drewnowski, A. (2015). Contribution of food prices and diet cost to socioeconomic disparities in diet quality and health: a systematic review and analysis. Nutrition Reviews, 73(10), 643–660. https://doi.org/10.1093/nutrit/nuv027

GBD 2015 Risk Factors Collaborators. (2016). Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. The Lancet, 388(10053), 1659–1724. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31679-8

GBD 2017 Diet Collaborators. (2019). Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. The Lancet, 393(10184), 1958–1972. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30041-8

Health Canada. (2019). Canada’s Food Guide. Health Canada, Ottawa, Ont., Canada. https://food-guide.canada.ca/en/

Kirkpatrick, S., & Tarasuk, V. (2003). The relationship between low income and household food expenditure patterns in Canada. Public Health Nutrition, 6(6), 589-597. doi:10.1079/PHN2003517

Lieffers, J. R. L., Ekwaru, J. P., Ohinmaa, A., & Veugelers, P. J. (2018). The economic burden of not meeting food recommendations in Canada: The cost of doing nothing. PLOS ONE, 13(4), e0196333. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0196333

Loewen, O. K., Ekwaru, J. P., Ohinmmaa, A., & Veugelers, P. J. (2019). Economic burden of not complying with Canadian food recommendations in 2018. Nutrients, 11(10), 2529. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11102529

Men F, Urquia ML and Tarasuk V. (2021). The role of provincial social policies and economic environments in shaping food insecurity among Canadian families with children. Preventive Medicine,148:106558. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106558.

Statistics Canada. (2010). Survey of Household Spending, 1997-2009 [Canada]. User guide and public-use microdata files, 2010. https://doi.org/10.25318/62m0004x-eng

Statistics Canada. (2014). Annual Demographic Estimates: Canada, Provinces and Territories 2014. Statistics Canada, 2014. Catalogue no. 91-215-X, no. 2. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/catalogue/91-215-X

Statistics Canada. (2021). Table 11-10-0125-01 Detailed food spending, Canada, regions and provinces. https://doi.org/10.25318/1110012501-eng

Tugault-Lafleur, C., & Black, J. (2019). Differences in the Quantity and Types of Foods and Beverages Consumed by Canadians between 2004 and 2015. Nutrients, 11(3), 526. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11030526

World Health Organization. (2011). Scaling up action against noncommunicable diseases: how much will it cost? https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/44706

World Health Organization. (2013). Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases 2013-2020. https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789241506236

World Health Organization. (2017). Updated Appendix 3 to the Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases 2013-2020. https://goo.gl/tyULjS

World Health Organization. (2018). Noncommunicable diseases. Fact sheet. www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases.

World Health Organization. (2020). Global Health Estimates. https://www.who.int/data/global-health-estimates