A Growing Problem: Is Canada’s Healthcare System Keeping Up with Newcomers?

Lauren Eastman, Sukhy K Mahl, Shoo K Lee

Abstract

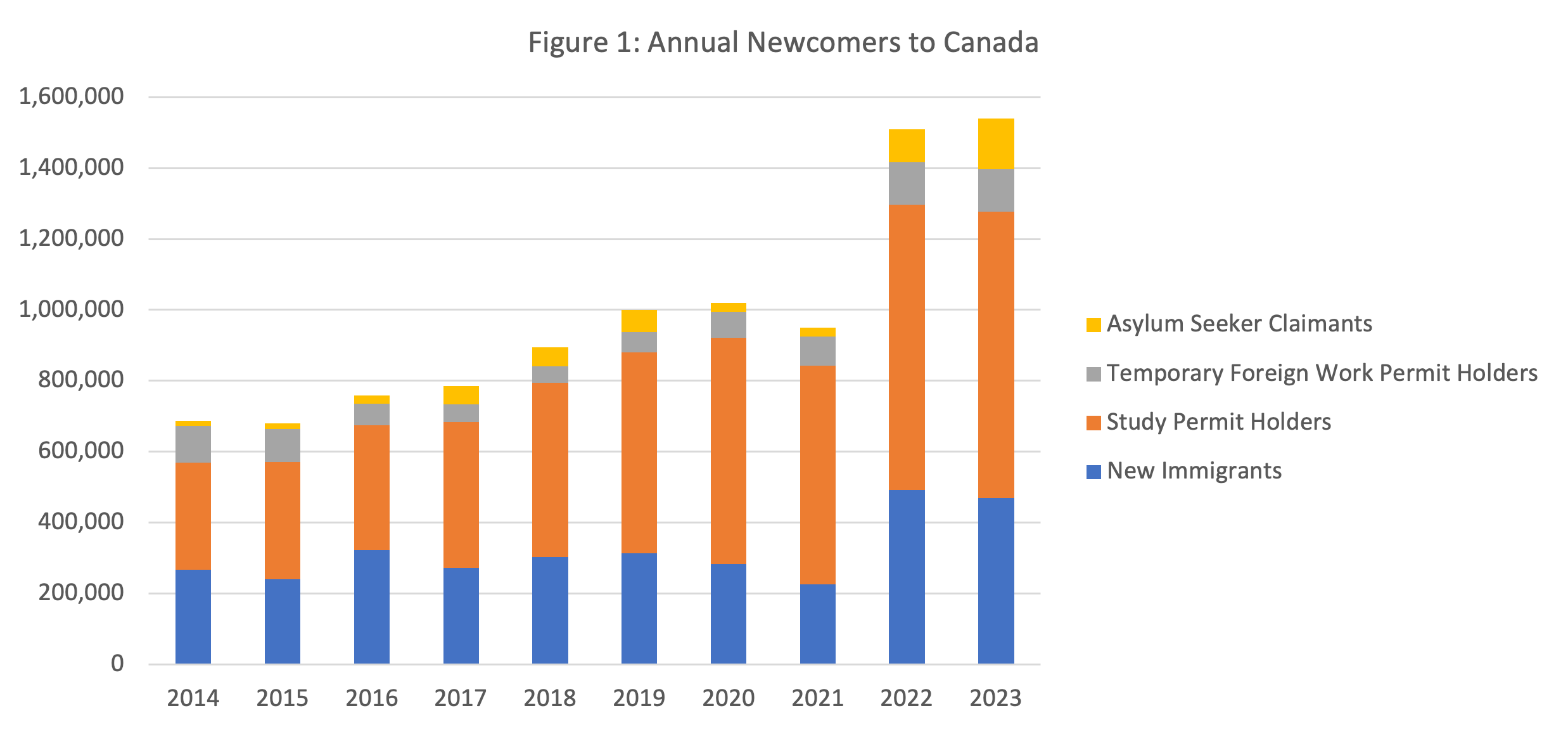

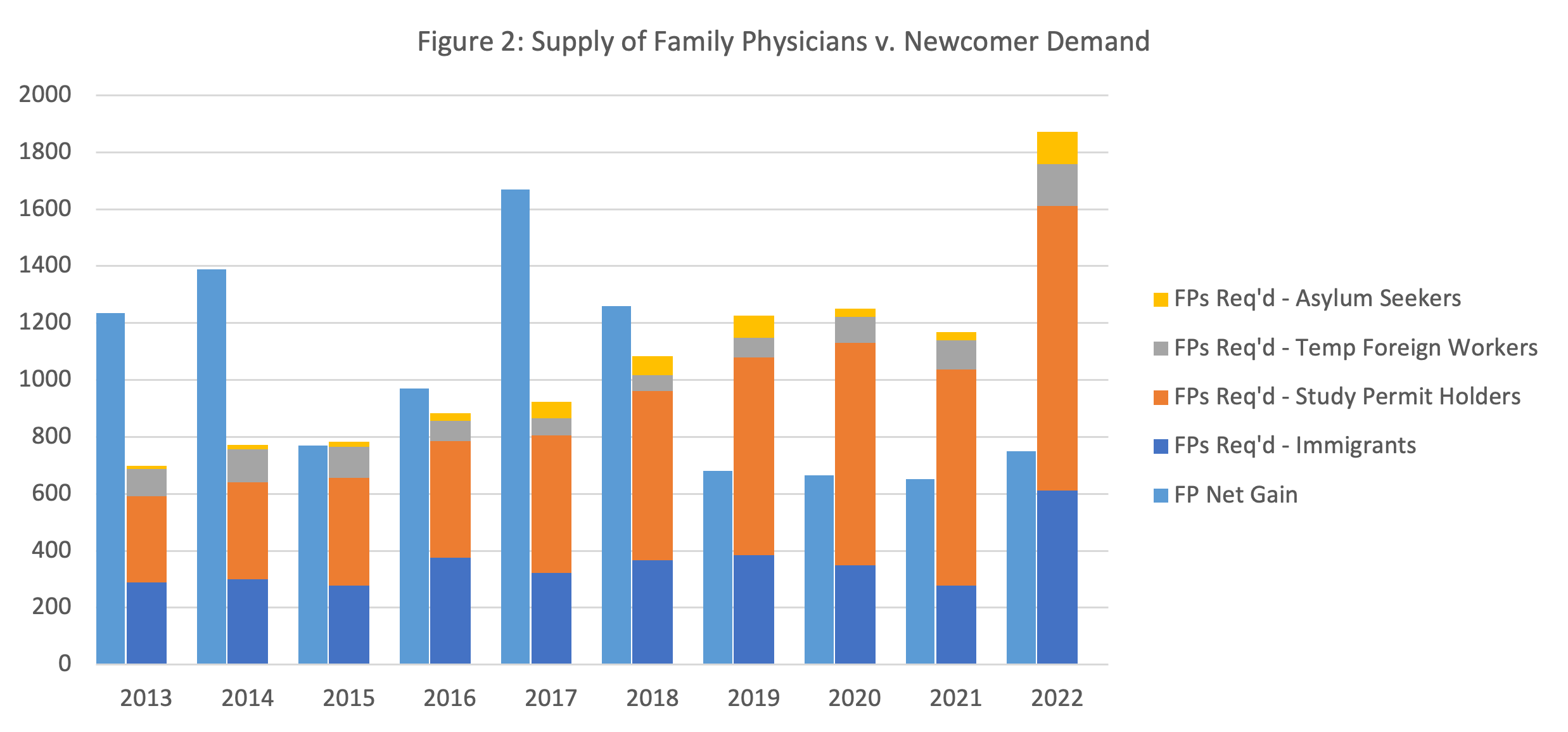

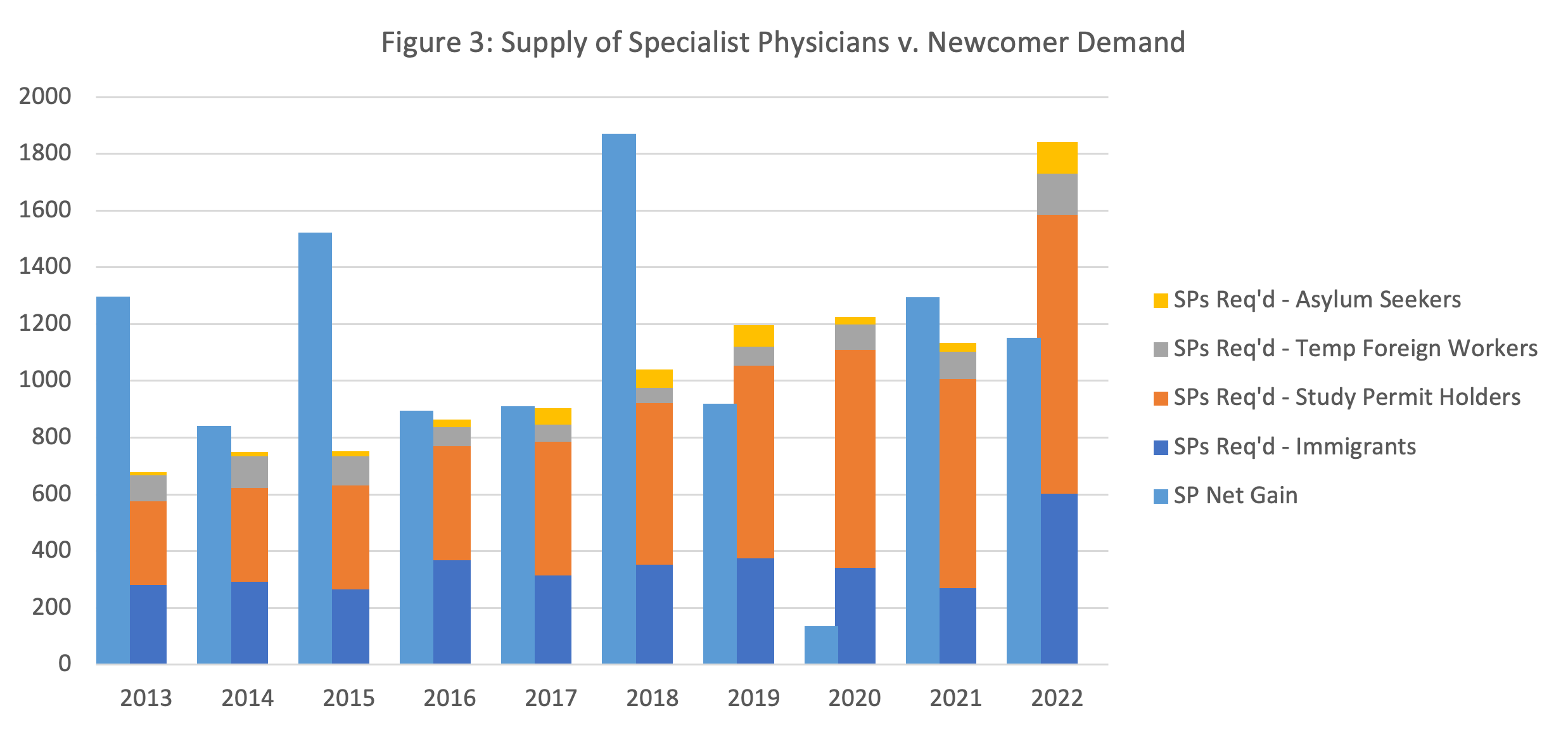

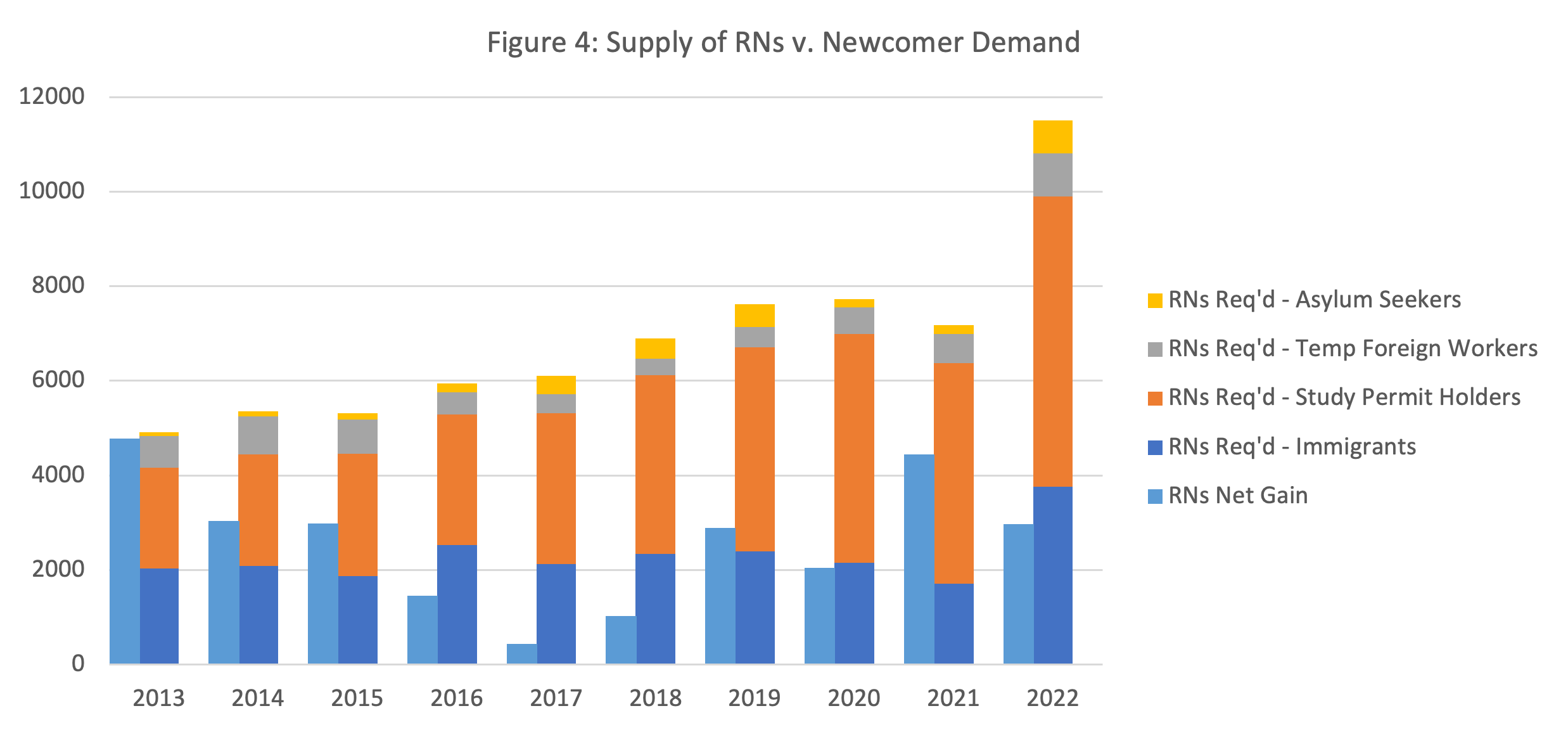

Summary: Canada’s population growth is ranked amongst the world’s highest, with the annual number of newcomers to Canada more than doubling over the last decade – from 686,000 in 2014 to 1,540,000 in 2023. Federal policy indicates sustained growth over the coming years. The newcomer demand for health human resources, including family physicians, specialists and registered nurses, far out-strips new supply in recent years, leading to a shortage of 1,122 family physicians, 690 specialists and 8,538 registered nurses in 2022. Immigration and healthcare resource policies should work in tandem to ensure the healthcare shortage facing Canadians is not exacerbated.

Authors credentials and affiliations:

- Lauren Eastman, BMSc, MD, CCFP, Family Physician, Assistant Professor and Assistant Program Director (Urban family medicine residency program) Department of Family Medicine University of Alberta

- Sukhy K. Mahl, MBA, Assistant Director MiCare Research Centre Mount Sinai Hospital

- Shoo K. Lee, MBBS, FRCPC, PhD, DHC, OC, Professor Emeritus University of Toronto, Honorary Staff Physician Mount Sinai Hospital

Correspondence: Dr. Shoo K. Lee, Department of Pediatrics, Mount Sinai Hospital, 19-231M, 600 University Avenue, Toronto, ON M5G 1X5, [email protected]

Disclosure: Although no specific funding has been received for this study, organizational support was provided by the Maternal-Infant Care Research Centre (MiCare) at Mount Sinai Hospital in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. MiCare is supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Team Grant (CTP 87518). The funding agency had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data; preparation, review or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Competing interests: The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Status: Peer reviewed.

Submitted: 26 JUN 2024 | Published: 15 JUL 2024

Citation: Eastman, Lauren; Mahl, Sukhy K; Lee, Shoo K (2024). A Growing Problem: Is Canada’s Healthcare System Keeping Up with Newcomers? Canadian Health Policy, JUL 2024. https://doi.org/10.54194/NEBL4084. canadianhealthpolicy.com.

Introduction

In November 2023, Canada’s federal government announced a plan to admit 1.5 million new immigrants into the country between 2024 and 2026. Canada’s population growth is now ranked among the world’s fastest, expanding much faster than any Group of Seven nation, China or India (Hertzberg and Kane 2023; Hopper 2024). While this rapid population growth strategy is aimed at economic growth, it is necessary to ensure that essential services, such as healthcare, grow in tandem to provide for such large population increases. In recent years, Canada’s healthcare system has faced widespread shortages, with 6.5 million Canadians unable to find a family physician, and lengthy waitlists for emergency and specialist referral care (Duong and Vogel 2023). In this article, we examine whether our healthcare system human resources are keeping pace with the demand from increasing newcomer populations in Canada and provide policy options to resolve potential problems.

Has the Canadian Healthcare System Kept Pace with Increasing Demand from Newcomers?

To determine whether the healthcare sector has grown sufficiently to meet the needs of newcomer groups in Canada, the last 10 years of data was analyzed for growth in newcomer groups, alongside growth in the number of family physicians (FPs), specialist physicians (SPs) and registered nurses (RNs). Newcomer groups include new immigrants, study permit holders, temporary foreign work permit holders and asylum seekers. Although some of these populations may be transient or temporarily residing within the country, their healthcare needs still need to be attended to during their time in Canada. Newcomer data was obtained from Statistics Canada and the Government of Canada websites (Statistics Canada, 2024; Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada 2024a, 2024b, 2024c). Figure 1 shows the trend in newcomer data from 2014 to 2023. Over this 10-year period, the number of immigrants has almost doubled, from 267,924 to 468,817 – a 75% increase in the last decade. The number of study permit holders also experienced tremendous growth, from 301,545 to 807,260 – a 168% increase. The numbers of temporary foreign work permit holders and asylum seeker claimants also grew from 103,910 to 119,825 (a 15% increase) and 13,445 to 143,785 (a 969% increase), respectively.

Family Physicians

Data for the number of FPs in Canada, as well as the number of FPs per 100,000 Canadians from 2013 to 2022 were obtained from the Canadian Institute of Health Information (CIHI)’s Scott’s Medical Database dataset (CIHI 2022b). The number of FPs per capita in each year was used to determine the equal number of FPs that would be required to meet newcomer needs for the following year. To determine whether the FP pool had grown sufficiently to meet the needs of newcomers, the year over year net gain of FPs in Canada was used. Figure 2 shows that since 2019, the FP net gain each year has not kept pace with newcomer requirements and the deficit continues to grow. In 2022, 1,872 new FPs were required to meet newcomer needs but there was a net gain of only 750 FPs in Canada – a 60% shortage.

Specialist Physicians

Data for the number of SPs in Canada and SPs per capita from 2013 to 2022 were also obtained from CIHI’s Scott’s Medical Database dataset (CIHI 2022b). Similar to FPs, the number of SPs per capita in one year was used to determine newcomer SP requirements in the following year. The annual net gain in SPs was employed to compare demand and supply. Figure 3 shows that the SP net gain in each year has been insufficient to meet newcomer requirements for three of the last four years. In 2022, 1,841 new SPs were needed to meet newcomer needs but there was a net gain of only 1,151 SPs in the same year – a 37% shortage. Indeed, in three of the six years previous to that, SP requirements for newcomers were only narrowly being met by the net gain in SPs each year. Consequently, similar to the situation for FPs, the recent increase in newcomers has exacerbated the shortage of SPs in Canada.

Registered Nurses

Data for the number of practicing RNs across Canada and population data were obtained from CIHI to calculate the number of RNs per capita (CIHI: Nursing in Canada 2022). Similar to FPs and SPs, the number of RNs per capita in one year was used to determine newcomer RN requirements in the following year. Data for Manitoba from 2019 onwards was suppressed due to significant under-coverage as a result of self-reporting, therefore 2018 data from the province was held constant and added to the total RN pool from 2019 to 2022. Figure 4 shows that RN net gain each year has been insufficient to meet newcomer requirements in each of the last ten years, with the largest deficits taking place in the latter years. In 2022, 11,512 new RNs were needed to meet newcomer needs but there was a net gain of only 2,974 RNs in the same year – a 74% shortage.

Limitations

It is possible that our analysis may have overestimated the health human resource requirements of newcomers because they are younger, healthier and need less healthcare than the average Canadian. However, it is also possible that newcomers, especially those from less developed countries, may have different health problems such as infectious, nutritional and chronic disease problems. Additionally, using the previous years’ per capita supply assumes that this supply rate is adequate, however, this is likely not the case. Regardless, our analysis suggests that there is a mismatch between the health needs of newcomers and the health human resource supply in recent years, and the problem will be compounded by the proposed policy of increased immigration in the coming years. Although there have been recent discussions to reduce the number of study permit holders in the country, the raised immigration targets will continue to keep newcomer figures high across Canada. Given that Canadians already experience massive shortages across the healthcare continuum, this trend will worsen the health care crisis currently facing all Canadians.

What Can be Done?

While immigration policy should not be dictated by healthcare resource availability, the two are interlinked and policies for immigration and healthcare must be aligned. If immigration policy is for newcomer groups to grow, then healthcare resources should also grow in tandem. Instead, in 2022, the national net gain in FP, SP and RN numbers was insufficient even to meet newcomer needs; with the shortage estimated at 1,122 FPs, 690 SPs and 8,538 RNs. To maintain the ‘status quo’ of healthcare human resource ratios in 2022, it is estimated that 124 FPs, 123 SPs and 727 RNs would be required per 100,000 newcomers. Both the federal and provincial governments should coordinate their policies to ensure that the supply of healthcare personnel is in alignment with immigration policy. This can be done by either increasing domestic output of healthcare personnel or increasing the intake of foreign trained healthcare. The latter may require appropriate credentialing and re-training to meet Canadian standards, and funding and retraining opportunities must be made available for them to enter the healthcare workforce. Newcomers may also often have specific healthcare needs that providers would require additional training to support. While this study only examined health human resources, similar policies should apply to health infrastructure such as hospital beds, diagnostic capacity, etc. Failure to align immigration and healthcare resource policies will worsen the health care crisis facing all Canadians, and potentially lead to public backlash against immigration.

References

Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI). Nursing in Canada, 2022 Data Tables. Retrieved 23 April 2024 from https://www.cihi.ca/en/registered-nurses.

Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI). Scott’s Medical Database Metadata: SMDB data table release (ZIP). 2022b. Retrieved 18 April 2024 from https://www.cihi.ca/en/scotts-medical-database-metadata.

Duong D, Vogel L. National survey highlights worsening Primary Care Access. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2023 Apr 23;195(16). doi:10.1503/cmaj.1096049

Hertzberg E, Kane LD. Population Growth in Canada Hits 3.2%, Among World’s Fastest, Bloomberg; 2023. Retrieved 16 April 2024 from https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-12-19/population-growth-in-canada-hits-3-2-among-world-s-fastest

Hopper, T. Canada-topping World Rankings Ottawa doesn’t want you to know about. National Post. 2024. Retrieved 29 April 2024 from https://nationalpost.com/opinion/canada-topping-global-rankings-ottawa-doesnt-want-you-to-know-about

Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada. Asylum claims 2023 [Internet]. Ottawa: Government of Canada; 2024c. Retrieved 16 April 2024 from https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/services/refugees/asylum-claims/asylum-claims-2023.html[4]

Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada. Temporary residents: Study permit holders – monthly IRCC updates. 2024a. Retrieved 9 April 2024 from https://open.canada.ca/data/en/dataset/90115b00-f9b8-49e8-afa3-b4cff8facaee[2]

Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada. Temporary residents: Temporary Foreign Worker Program (TFWP) and International Mobility Program (IMP) work permit holders – monthly IRCC updates. 2024b. Retrieved 9 April 2024 from https://open.canada.ca/data/en/dataset/360024f2-17e9-4558-bfc1-3616485d65b9[3]

Statistics Canada. Table 17-10-0008-01 Estimates of the components of demographic growth, annual. 2024. Retrieved 9 April 2024 from https://doi.org/10.25318/1710000801-eng[1]