Community Trust and Public Health Compliance: COVID-19 Experiences in Newfoundland and Labrador

Thaneswary Rajanderan PhD1*, Rodney Russell PhD2, Chand S Mangat PhD3, Douglas Howse BSc4, Cheryl PZ Foo MD4, Atanu Sarkar PhD1

ABSTRACT

Objectives: The COVID-19 pandemic profoundly affected global healthcare systems, necessitating effective infectious disease control measures. Understanding specific populations’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAP) relating to COVID-19 is crucial for implementing public health interventions. Since Newfoundland and Labrador (NL), Canada has a unique socio-geographic context and high healthcare expenditures per capita, a KAP study is needed to understand how COVID-19 impacted local communities and its influence on public health measures. Methods: In-depth interviews were conducted with 100 NL resident participants aged 18–76 years between August 2022 and January 2023 to investigate their experiences with COVID-19 through a phenomenological and KAP framework. Results: The study identified three main themes: COVID-19, knowledge built on locally trusted sources and experiences, social dynamics shaping attitudes towards COVID-19, and the need for public health tools to improve practices around COVID-19. Key findings include reliance on local news for information, mental health impacts, high compliance with health measures, and challenges in at-home care and recovery. Some challenges include the need for regular communication, accessible mental health support, and COVID-19 at-home care tools. Conclusion: The unique experiences and KAP of COVID-19 in NL highlight the importance of understanding regional differences to improve COVID-19 public health interventions. Targeted interventions that focus on transparent communication, at-home COVID-19 care tools, and accessible mental health support should be explored in the context of regional public health support for sustaining a healthy population and mitigating future outbreaks in similar contexts.

Authors credentials and affiliations:

- Population Health and Applied Health Science, Faculty of Medicine, Memorial University of Newfoundland and Labrador.

- Biomedical Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, Memorial University of Newfoundland and Labrador.

- JC Wilt Infectious Diseases Research Centre, National Microbiology Laboratory, Winnipeg.

- Department of Health and Community Services, Government of Newfoundland and Labrador.

* Corresponding Author (email [email protected] and phone 17099866068)

Funding: This work was supported by the Seed, Bridge and Multidisciplinary Fund [grant number 20230226] and the Faculty of Medicine Dean’s Fellowship from Memorial University of Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada, to support the graduate student.

Conflict of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare relevant to this article’s content.

Ethics approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Health Research Ethics Board in Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada (# 2022.110) and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.”

Consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Data and material: The data underlying this article are available in the article.

Author contributions: All authors contributed to the study’s conception and design. Thaneswary Rajanderan prepared the material, collected the data, and performed the analysis. Atanu Sarkar supervised Thaneswary Rajanderan in all the steps of the research project. Thaneswary Rajanderan wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgment: The authors are grateful to Danni Kaitlyn Garrison for advice and support for the project. Participant recruitment was aided by local organizations such as Seniors NL, CAPE NL, Multicultural Women’s Organization of NL, healthcare workers groups, and student groups at Memorial University of Newfoundland.

Status: Peer reviewed.

Submitted: 09 AUG 2024 | Published: 26 SEP 2024

Citation: Rajanderan, Thaneswary; and Rodney Russell, Chand S Mangat, Douglas Howse, Cheryl PZ Foo, Atanu Sarkar. (2024). Community Trust and Public Health Compliance: COVID-19 Experiences in Newfoundland and Labrador. Canadian Health Policy, SEP 2024. https://doi.org/10.54194/JZCV5288. canadianhealthpolicy.com.

INTRODUCTION

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (commonly known as SARS-CoV-2) is the strain of coronavirus that caused the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. The latest global report (as of 24th July 2024) by the World Health Organization (WHO) has recorded more than 775 million COVID-19 cases and seven million deaths (World Health Organization, 2024). Apart from this dramatic loss of human life worldwide, the pandemic has significantly impacted healthcare systems and posed unprecedented challenges to public health, economies, and social norms (Zhu et al., 2020; Rothe et al., 2020).

Knowledge, attitude, and practice (KAP) studies can help evaluate a population’s behavioural and social norms concerning certain diseases or interventions (Muleme et al., 2017). This helps ensure appropriate and cost-effective interventions, especially at the provincial and municipal levels (Devkota et al., 2021). A shortage of intensive care units, respirators, and personal protective equipment greatly impacted the COVID-19 patient experiences worldwide. While severe cases resulted in hospitalization, most COVID-19 cases were asymptomatic or mild and required at-home care instead (Government of Canada, 2022). This means many COVID-19 patients recovered at home and were more influenced by the changing COVID-19 restrictions and quarantine plans (Dainty et al., 2023). The changing COVID-19 policies and availability of healthcare services, such as isolation plans, vaccinations and testing, greatly impacted the lived experiences of COVID-19 patients and their at-home recovery process (Dainty et al., 2023). So, it is essential to consider these experiences when adopting new COVID-19 policies. Our study has focused on the lived experiences and KAP of COVID-19 in Newfoundland and Labrador (NL).

Understanding the lived experience of COVID-19 patients is essential to improve healthcare services within a population. A UK study showed that understanding their COVID-19 patients’ experiences and perspectives could address gaps and concerns within their local healthcare systems (Buttery et al., 2021). For example, they suggested plans to increase patient communications to address uncertainties and identify patient-experienced prohibitive barriers to getting treated (Buttery et al., 2021). Another study focused on patients’ experiences and feelings while infected with COVID-19 and how the infection had impacted their quality of life (Quigley et al., 2021). They identified the challenges patients experienced, such as psychosocial stresses (isolation, loss of motivation, anxiety, and sadness) and physical manifestations of the disease (Quigley et al., 2021). This knowledge can improve the quality of care for COVID-19 patients.

A COVID-19 national survey in Canada found that vaccine hesitancy was the highest among young adults (18–39 years) compared to older people, so public messaging about COVID-19 had to cater more towards this group to shift their attitudes toward vaccines (Benham et al., 2021). In this survey, researchers identified distinct clusters of individuals with varying vaccine hesitancy types based on their knowledge and attitudes toward vaccines. The researchers show associations among knowledge, attitude, and practices, where the knowledge of COVID-19 vaccines can influence an individual’s attitude and practices concerning vaccine uptake. In other national COVID-19-related surveys, researchers found that KAP regarding COVID-19 is complex due to the diverse socio-demographic characteristics of populations (Brankston et al., 2021; Leigh et al., 2022). However, these national surveys categorized the four eastern provinces, NL, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island, as one Atlantic region demographically. When looking at regional differences in the study, the Atlantic region was compared to other provinces, such as Ontario and British Columbia, which can lead to generalization (Parsons Leigh et al., 2020). Also, surveys on COVID-19 KAP thus far have all been quantitative in nature, with a lack of exploration into how the underlying phenomena influence health behaviours (Muleme et al., 2017; Christie & Mason, 2011). Even though these quantitative surveys provide valuable information about differences in KAP regarding age, gender, and location, qualitative studies are needed to explore the reasoning behind these differences to personalize public health interventions at provincial and municipal levels (Muleme et al., 2017).

In NL, the first COVID-19 case was reported on March 14, 2020, which initiated the COVID-19 outbreak (Linka et al., 2020). Health outcomes due to COVID-19 can be exacerbated by pre-existing health conditions such as obesity, cancer, and diabetes (Mayo Clinic, 2024). The infection also disproportionately impacts older adults and can result in severe diseases that require extensive care in a hospital setting. Compared to other provinces, NL has a higher rural population (42% vs the Canadian average of 18%) with limited access to emergency healthcare in remote areas (Charbonneau et al., 2022). NL’s population has a higher proportion of aging individuals (24%) compared to the national average (19%) (CIHI, 2023). Even though NL has one of the highest per capita healthcare expenditures in Canada (CAD 10,333), well above the national average (CAD 8,740), the province still ranks lowest for overall health indicators among Canadian provinces (CIHI, 2023; The Conference Board of Canada, 2023). For example, NL has higher occurrences of cancer (695 cases per 100,000 people in 2019) and obesity (39,400 cases per 100,000 people in 2018) compared to the national average of 554 cases per 100,000 people in 2019 and 27,200 cases per 100,000 people in 2018, respectively (Government of Canada, 2024; Lytvyak et al., 2022). Given the significant health expenditure and poor health outcomes, the COVID-19 outbreak could have been highly detrimental in NL as the local healthcare systems could have become quickly overwhelmed. However, NL had a lower-than-average incidence rate of COVID-19 at 10,868 per 100,000 population and a mortality rate from COVID-19 at 76 per 100,000 population compared to the national averages of 12,360 per 100,000 population and 148 per 100,000 population, respectively (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2024). To understand this paradox, it is essential to phenomenologically explore lived experience and identify KAP regarding COVID-19 in the province and use that knowledge to inform future public policy around emergency health plans for outbreaks.

METHODS

Conceptual framework:

The study was conducted and analyzed using phenomenology from a constructivist research paradigm to capture best the lived experience of COVID-19 residents in NL. The ‘phenomena’ in this study is COVID-19, specifically in NL, so using this paradigm, phenomena are described among participants in our study setting to answer the research questions (Groenewald, 2004). This allowed for an in-depth understanding and interpretation of the complexity of human behaviour around COVID-19 in NL, which can determine effective interventions to improve and protect community health (Renjith V et al., 2021). A KAP framework was then used to organize further and describe participants’ experiences (Benham et al., 2021).

Target population, research setting and sample size:

The purpose of the study was to describe the COVID-19 KAP of NL residents (August 2022 to January 2023) aged 18 years and older. In-depth interviews were conducted, and it was determined that knowledge saturation was reached, which was when there were no new findings with new interviews (Saunders et al., 2017).

Recruitment strategy:

A convenience sampling approach was adopted because the participants were recruited via listservs and printed posters delivered to local community-based organizations (such as Seniors NL, Association for New Canadians, and student-interest groups at Memorial University of Newfoundland) (Bevan et al., 2021; Papagiannis et al., 2020). COVID-19 patients and non-patients (the two population groups) were recruited using the same sampling approach, with deferring inclusion criteria. COVID-19 patient participants were over the age of 18 years and had been previously diagnosed with COVID-19 (presented a positive COVID-19 test), while non-patient participants had to be over the age of 18 and not have been previously diagnosed with COVID-19 up to the time of the study. Once the potential participants contacted the researcher through email or phone, online consent was obtained via email. All the participants were compensated with CAD 25 gift cards for their involvement in the study.

Research instrument:

The interview guide for the non-COVID-19 patients focused on their knowledge of COVID-19 and related topics, their attitude towards the disease and practices around it, their experience with public health restrictions and vaccines, and their actions to prevent COVID-19 infection throughout the pandemic (Supplementary TABLE 1A). In terms of COVID-19 patients, the interview guide focused on patients’ experiences prior to diagnosis, testing, process of care, recovery and challenges associated with COVID-19 (Supplementary TABLE 2A). The guide was based on previous studies exploring perceptions of COVID-19 (Parsons Leigh et al., 2020; An et al., 2021), and it was further validated before the interviews through mock interviews with colleagues.

Data analysis:

All individual interviews were transcribed (via Otter.Ai, an online meeting notetaking platform), and an in-depth thematic analysis was performed using Atlas.Ti (Version 23.4.0), a qualitative data analysis software for research (Otter.ai, Inc., 2023; ATLAS.ti, 2023). The researcher verified all transcriptions and coding to ensure that any errors were addressed. Thematic analysis was conducted inductively, based on previous literature, and deductively based on the dataset (Brankston et al., 2021; Leigh et al., 2022).

Ethics:

All recruitment, consent forms, incentives, question guides, analysis, and data management strategies followed the guidelines and required approval from the Newfoundland and Labrador’s Health Research Ethics Board, which was processed in 2022 (# 2022.110).

RESULTS

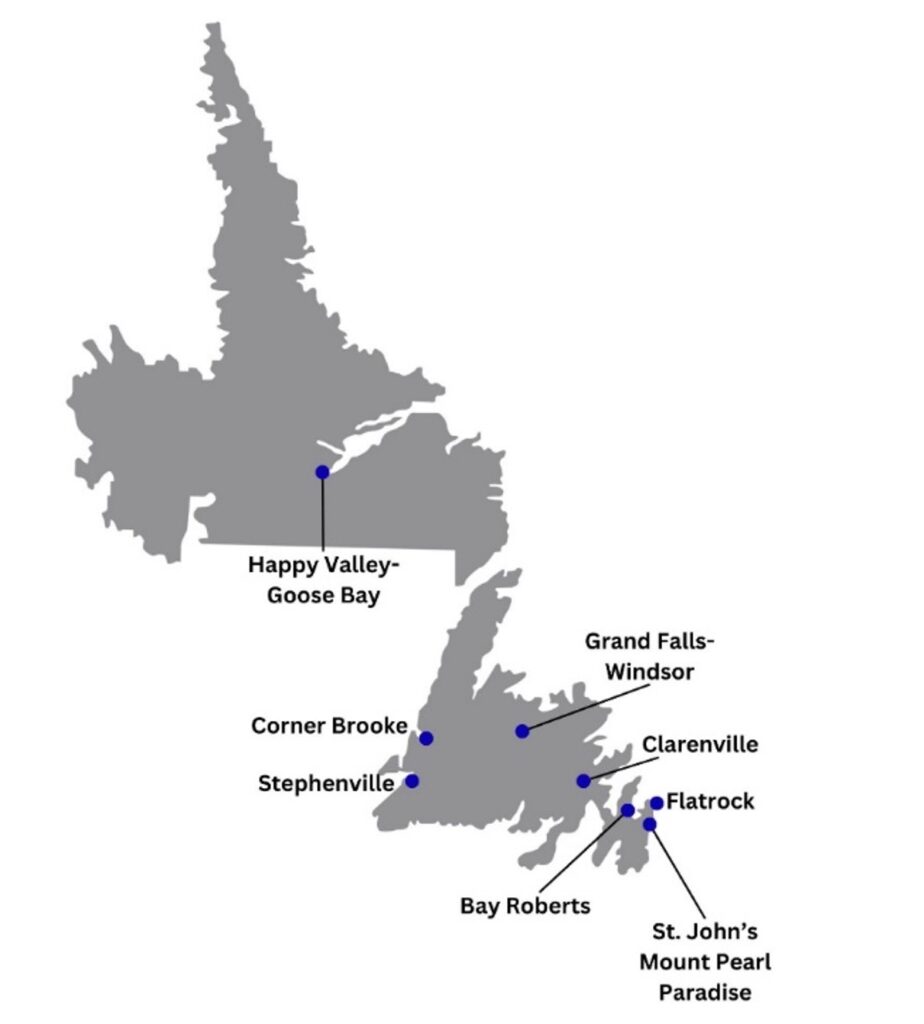

There were 100 participants between 18 and 76 years old, with an average age of 37 (TABLE 1). There were 47 participants who did not have COVID-19 (non-patients) and 53 who were infected with COVID-19 (patients) before the interviews. It should be noted that 87 participants were from St. John’s metropolitan area (approximately 200,000 people, which is 58% of the total population in 2022) compared to rural regions of NL, such as Flatrock (FIGURE 1). TABLE 1, which shows the participant summary, also divides the participants into mutually exclusive occupational groups: students, healthcare workers, non-healthcare workers and retired. Caucasian-identifying participants comprised most of the sample size, followed by South Asian-identifying participants. The average length of the interviews was 20.58 minutes.

Theme 1: COVID-19 knowledge built on locally trusted sources and experiences

Definition: Described types and richness of COVID-19-related knowledge among participants based on their media consumption, trust of information, and personal experiences with the disease.

Most participants could describe COVID-19 and its symptoms, vaccines, and transmission mode; however, participants from all occupational groups besides healthcare workers interchangeably used the terms SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19. The participants also heavily relied on trusted local news (such as broadcast news channels on TV) and provincial sources for COVID-19 information over social media (such as Meta (Facebook) and X (Twitter)) and international news sources (such as CNN). However, a few participants, primarily younger adults regardless of gender and middle-aged women, still subscribed to the information on these platforms, especially when their family and friends directly shared it with them. Typically, these participants also believed in some known COVID-19 misinformation about the disease, such as its origin and how it is transmitted.

| TABLE 1: Participant demographic distribution (N = 100) | |||

| Characteristics | Non-patients Count (%) | COVID-19 patients Count (%) | |

| Gender | Male | 17 (36) | 15 (28) |

| Female | 30 (64) | 37 (70) | |

| Non-binary | – | 1 (2) | |

| Age in years | 18-19 | 1 (2) | – |

| 20-29 | 14 (30) | 24 (45) | |

| 30-39 | 11 (23) | 14 (26) | |

| 40-49 | 6 (13) | 8 (15) | |

| 50-59 | 8 (17) | 4 (8) | |

| 60-69 | 5 (11) | 3 (6) | |

| 70-79 | 2 (4) | – | |

| Occupation | Student | 21 (44) | 26 (49) |

| Non-healthcare worker** | 11 (24) | 12 (23) | |

| Healthcare worker | 6 (13) | 14 (26) | |

| Retired | 9 (19) | 1 (2) | |

| Ethnicity | Caucasian | 29 (63) | 39 (74) |

| South Asian | 11 (23) | 6 (11) | |

| East Asian | 2 (4) | 3 (5) | |

| Indigenous groups | 2 (4) | 2 (4) | |

| Middle Eastern | 2 (4) | 1 (2) | |

| African | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | |

| Latin | – | 1 (2) | |

| * Non-healthcare workers include teachers, business owners, retail workers, etc. | |||

Subtheme 1.1 Personal experience of directly dealing with COVID-19

Definition: Knowledge built upon specifically by personal experience of being a COVID-19 patient (which includes testing, diagnosis, and recovery) or acting as a caregiver (active role in caring for a family member with COVID-19 in the same household).

Before infections, most participants had some preconceived notions about the severity of diseases. Often, it was assumed that infection would be mild when vaccinated against SARS-CoV-2. However, COVID-19 infections still have a negative impact on the quality of life regardless of the severity of the disease. Participants described quality of life as encompassing their ability to perform tasks such as working and socializing to their usual standards, which deferred in levels among participants. For example, the infection affected some participants’ active social life, interacting with friends and attending events, thus affecting their quality of life. In terms of physical health, most participants had flu-like symptoms for three to five days. However, fatigue, cough and general “body aches” persisted for weeks, which impeded day-to-day activities such as working and performing household chores. When discussing mental health, constant fatigue and the isolation mandates posed a challenge for participants. They were not able to maintain active lifestyles (such as actively exercising) and avail themselves of their regular stress outlets (such as socializing and running). Another symptom that posed a challenge for participants was “brain fog,” which is a general state of not being able to focus on their regular tasks, which further worsens their mental health and the term was explicitly used among participants when describing this phenomenon.

FIGURE 1. Newfoundland and Labrador locations (municipalities) of the participants in the study.

Theme 2: Social dynamics shaping attitudes towards COVID-19

Definition: Described positive and negative attitudes surrounding COVID-19 based on knowledge and how it impacted the day-to-day life of participants from a social perspective.

Overall, the participants experienced fear when it came to personal health, familial health, and job security. Regarding physical health, participants were more worried about the health of their loved ones, especially their older parents, than their own. This resulted in them taking additional COVID-19 measures, such as masking and social distancing from their close friends and family. A few participants (individuals living in urban regions and typically below 65 years old) experienced unemployment, which caused anxiety as well. This unemployment was due to layoffs brought on by COVID-19, which caused certain places to downsize or shut down. Despite the expressed stress and fear, participants, especially women and older individuals, exhibited an abundance of trust in the COVID-19 public health measures put in place by the local health authorities. Participants described the abundance of trust as having faith in public health measures, not necessarily because they understand the intricate environment behind it but because they believe that local authorities have done their due diligence to verify its effectiveness. By keeping themselves informed, all participants believed in the effectiveness of social distancing, masking, and vaccines. Even though they were uncertain about the rationale behind some public health measures (such as numbered bubbles), especially later in the pandemic, participants still firmly adhered to them. Some individuals over the age of 65 years pointed out that the continuous airing of daily or weekly COVID-19 updates by local public health authorities helped ease their fear and increase their trust in these public health authorities.

All patient interviewees underwent home isolation and at-home care when responding to infections. At-home care included home remedies such as tea, cold compresses, and over-the-counter drugs to manage the symptoms. The level of at-home care greatly varied based on the participant’s social and cultural dynamics. For example, participants with immigrant roots typically practice traditional medicine, such as consuming turmeric and ginger. Even though patients and caregivers (family members of patients who aid them at-home care) found the overall experience primarily positive, there were still instances of uncertainty and fear. From the patient’s perspective, the participants indicated that they heavily relied on their family and friends when recovering from COVID-19. This reliance comes in the form of mental and physical support, such as obtaining groceries and daily communication to cope with isolation. Caregiving ensured the participants had medicines, food, and company over the phone while isolating at home. Immigrant participants whose families were in other countries could continuously video call them to check up on them. However, being infected with COVID-19 also meant some participants were emotionally distressed and felt guilty if the disease was transmitted to their loved ones. Participants expressed that one of their biggest fears was getting people around them sick, especially those at risk for severe infection.

Theme 3: Need for public health tools to improve practices around COVID-19

Definition: Described general participant behaviours when trying to avoid infection or re-infection of COVID-19 and explored public health gaps identified by participants.

Most participants were isolated at home and only briefly interacted with the healthcare systems, primarily at testing sites. So, more relied on at-home care and remedies for COVID-19 recovery. Participants used resources and media briefs published by local health authorities to inform them about their isolation periods and the at-home care process. Even though interactions with healthcare providers were brief, they were positive experiences in general. Some participants who visited the test sites had continuous support via phone calls from the COVID-19 local response team to ensure they were recovering properly. Overall, participants trusted the local health authorities’ public health measures for COVID-19 and understood their importance. For example, participants described tuning into NL COVID-19 media briefs to watch the daily updates directly from the chief medical officer and the provincial premier. However, some still felt there was a lack of communication with COVID-19 patients to inform them of current measures and isolation periods towards the end of the pandemic in December 2022. For example, the COVID-19 updates were described as sparse and more complicated to look for on any form of media. So, when participants were infected, they were not able to quickly look up current restrictions for reporting and at-home isolation.

Subtheme 3.1: High compliance to public health measures due to trust in local authorities

Definition: Described how strictly participants followed COVID-19 public health guidelines, primarily based on their trust in local officials and the effectiveness of the measures.

Most participants, regardless of age, gender, and occupation, complied with public health restrictions and took additional measures such as social distancing and masking even when it was not mandated, especially early in the pandemic. However, some participants living in rural NL mentioned low compliance with these measures, particularly while travelling, such as not properly social distancing when in public. They believed their close-knit societies, due to the small size of the communities’ populations, were the possible reason for such laxity. They felt safer as they believed their communities were free from COVID-19 infections and that their neighbours were being equally careful. This led to these participants masking and social distancing less (than the urban population).

Subtheme 3.2: Communication as a means to reassure and inform the public

Definition: Incidents where communicative materials (such as infographics and general knowledge translation) were needed to inform the public of the science behind specific measures and dispel misinformation.

Older participants (over the age of 60 years) typically expressed heightened concern about the risk of COVID-19 and expressed less vaccine hesitancy than younger participants. This was primarily because older participants encountered higher mortality and hospitalization rates due to COVID-19 compared to the rest of the population. Considering this, most participants, especially older participants, expressed interest in any additional COVID-19 vaccine boosters in the future. However, some participants, such as parents of younger children, were hesitant about vaccines. They said they would probably wait a few months before giving them boosters to observe the side effects or that they would only receive them when required. These participants primarily consumed social media content and less government information on COVID-19.

DISCUSSION

This study showed that the patient experiences and KAP around COVID-19 in NL are complex and unique compared to other parts of the country. The themes and subthemes highlighted residents’ lived experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic and existing gaps while implementing public health measures to control the pandemic.

Regarding COVID-19 general KAP, participants relied heavily on trusted local news sources for information about COVID-19 and were well-informed about the basics of COVID-19. However, a significant few participants still believed in some misinformation (such as where the virus originated or how it can be transmitted) about COVID-19 from social media, especially when shared by people they trusted. Therefore, continuous educational resources should be dedicated to teaching NL residents to be aware of and identify COVID-19 misinformation. There are still some disparities between older and younger generations regarding their perception of the risk that the COVID-19 disease presents, which is similar to the findings of Leigh et al. on demographical differences (2022). This could decrease public health measure compliance and vaccination over time if not addressed, with more targeted public messaging towards these groups required to prevent that outcome. Fear and anxiety among participants were mostly experienced by participants when it came to the health of their loved ones and job security during the pandemic. An increase in policies to protect individuals vulnerable to unemployment and services that protect physical well-being is needed. This can include continuous access to testing and essential needs for the individuals most susceptible to COVID-19. When looking at practices relating to COVID-19, the most important focus should be continuous communication and updates on COVID-19 (such as disease risk, vaccines, knowledge translation on the science around the virus, etc.) within municipal communities, as most participants needed clarification on the rationale of specific public health measures. This will aid residents in preparing for and changing their practices when there is uptake in the spread of COVID-19.

The COVID-19 patient participants in this study were not hospitalized and recovered at home, so the study analysis focused more on outpatient care. Based on the results, the critical challenges patients faced included (1) prolonged symptoms such as fatigue, (2) emotional distress when managing the disease at home, and (3) the need for public health and communication resources to inform the recovery process for COVID-19. Even though most participants experienced mild symptoms, most reported being fatigued for prolonged periods post-recovery, similar to other studies (Buttery S et al., 2021); this could impact the patient’s quality of life even months after recovery in terms of their personal and professional lives. Most participants experience distress at some points in their recovery process, especially when dealing with their mental health during isolation, fear of spreading the disease to loved ones and having to step back from their regular duties for an extended period. So, there is still a need to develop accessible mental health support for COVID-19 patients. Similar to the findings of Dainty et al., there is a need for communication and COVID-19 public health guidelines to be more accessible for patients due to the shifting nature of COVID-19 measures with the frequency of cases (2023). For example, mental health support links can be shared regularly through social media and advertised at strategic locations such as healthcare centres, schools and workplaces.

Previous studies focus on quantitative or cross-sectional surveys of known KAP around COVID-19. Earlier studies of COVID-19 KAP in Canada were primarily quantitative surveys that identified differences in KAP nationwide (Brankston et al., 2021; Leigh et al., 2022). However, there has been a lack of qualitative studies that explore the in-depth reasoning behind these differences, which the thematic analysis of this study highlights. For example, Brankston et al. found that vaccine hesitancy was high among individuals aged between 18 and 39 years. While there was significant statistical analysis to show these associations. There was a gap when explicating the rationale behind this finding outside of the pre-determined questions in the surveys. For example, in this study, we found that younger adults experienced vaccine hesitancy because they feared the vaccine’s side effects on their children and not necessarily themselves, in addition to having a low perceived risk of disease. Similarly, there are multiple studies looking at severe COVID-19 cases or experiences of hospitalized individuals instead of COVID-19 with at-home care. Since most COVID-19 cases are mild or asymptomatic and do not require in-hospital care, it is essential to reflect on the experiences of these individuals to improve COVID-19 public health measures and develop tools for at-home COVID-19 care. Cross-sectional surveys in Canada typically group all provinces in Atlantic Canada as one, even when looking at regional differences (Parsons Leigh et al., 2020). The four provinces making up the Atlantic region have varying demographical and geographical differences; therefore, the generalization across these regions can result in an inaccurate representation of COVID-19 KAP and patient experiences in NL. These strict measures included province-wide travel restrictions, high compliance with masking, and social distancing orders. So, this study shows that despite NL experiencing high rates of co-morbidities such as cancer and obesity, the province maintained lower rates of COVID-19 compared to the Canadian averages because residents highly adhere to the COVID-19 measures introduced by the local health authorities. The residents of NL responded positively to changes in public health measures throughout the pandemic due to the high level of trust in local health authorities built throughout the pandemic, a trend that was not seen in other provinces in Canada (Leigh et al., 2022). Identifying the gaps, such as the need for at-home care tools, public communication pieces, perceived risk of disease, vaccine hesitancy and differences in compliance with health measures, can help maintain trust and improve the well-being of NL residents against COVID-19.

LIMITATIONS

Recruitment was based on convenience and snowball sampling, and there would always be volunteer bias, which could result in a lack of variety in the sample; however, a more significant number of participants were recruited to address this issue until knowledge saturation was reached.

CONCLUSIONS

This study highlights the importance of in-depth qualitative research exploring the lived experiences of COVID-19 patients and residents of NL when informing COVID-19 health measures. The gaps identified highlight the unique COVID-19 experiences in NL, such as high compliance with COVID-19 measures, a strong sense of community, heightened emotional distress during infection and trust in local health authorities. These findings show a need for personalized COVID-19 plans based on regional demographical differences, as this will help predict resident and patient behaviour during pandemic situations and in response to healthcare protocols. So, future directions include further exploring the challenges the study identified and crafting communication and public health resources to address them.

REFERENCES

ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH. (2023). ATLAS.ti Mac (version 23.2.1) [Qualitative data analysis software]. ATLAS.ti. https://atlasti.com/

Benham, J. L., Atabati, O., Oxoby, R. J., Mourali, M., Shaffer, B., Sheikh, H., Boucher, J. C., Constantinescu, C., Parsons Leigh, J., Ivers, N. M., Ratzan, S. C., Fullerton, M. M., Tang, T., Manns, B. J., Marshall, D. A., Hu, J., & Lang, R. (2021). Covid-19 vaccine–related attitudes and beliefs in Canada: National cross-sectional survey and cluster analysis. JMIR Public Health and Surveillance, 7(12). https://doi.org/10.2196/30424

Bevan, I., Stage Baxter, M., Stagg, H. R., & Street, A. (2021). Knowledge, attitudes, and behavior related to covid-19 testing: A rapid scoping review. Diagnostics, 11(9), 1685. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics11091685

Brankston, G., Merkley, E., Fisman, D. N., Tuite, A. R., Poljak, Z., Loewen, P. J., & Greer, A. L. (2021). Socio-demographic disparities in knowledge, practices, and ability to comply with covid-19 public health measures in Canada. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 112(3), 363–375. https://doi.org/10.17269/s41997-021-00501-y

Buttery, S., Philip, K. E., Williams, P., Fallas, A., West, B., Cumella, A., Cheung, C., Walker, S., Quint, J. K., Polkey, M. I., & Hopkinson, N. S. (2021). Patient symptoms and experience following COVID-19: Results from a UK-wide survey. BMJ Open Respiratory Research, 8(1). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjresp-2021-001075

Charbonneau, P., Martel, L., & Chastko, K. (2022, February 9). Population growth in Canada’s rural areas, 2016 to 2021. Government of Canada, Statistics Canada. https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2021/as-sa/98-200-x/2021002/98-200-x2021002-eng.cfm

Christie, F. T., & Mason, L. (2011). Knowledge, attitude and practice regarding vitamin D deficiency among female students in Saudi Arabia: A qualitative exploration. International Journal of Rheumatic Diseases, 14(3). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1756-185x.2011.01624.x

CIHI. (2023). Your Health System: Newfoundland and Labrador. https://yourhealthsystem.cihi.ca/hsp/indepth?

The Conference Board of Canada. (2023, April 24). Health. The Conference Board of Canada. https://www.conferenceboard.ca/hcp/health-aspx/

Dainty, K. N., Seaton, M. B., O’Neill, B., & Mohindra, R. (2023). Going home positive: A qualitative study of the experiences of care for patients with covid-19 who are not hospitalized. CMAJ Open, 11(6). https://doi.org/10.9778/cmajo.20220085

Devkota, H. R., Sijali, T. R., Bogati, R., Clarke, A., Adhikary, P., & Karkee, R. (2021). How does public knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors correlate in relation to COVID-19? A community-based cross-sectional study in Nepal. Frontiers in Public Health, 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.589372

Government of Canada, S. C. (2022, April 27). In the midst of high job vacancies and historically low unemployment, Canada faces record retirements from an aging labour force: Number of seniors aged 65 and older grows six times faster than children 0-14. The Daily. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/220427/dq220427a-eng.htm

Government of Canada, Statistics Canada. (2024, January 31). Number and rates of new cases of primary cancer, by cancer type, age group and sex. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1310011101

Government of Canada. (2022, June 22). COVID-19 signs, symptoms and severity of disease: A clinician guide. Canada.ca. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/2019-novel-coronavirus-infection/guidance-documents/signs-symptoms-severity.html

Groenewald, T. (2004). A phenomenological research design illustrated. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 3(1), 42–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690400300104

Leigh, J. P., Brundin-Mather, R., Soo, A., FitzGerald, E., Mizen, S., Dodds, A., Ahmed, S., Burns, K. E., Plotnikoff, K. M., Rochwerg, B., Perry, J. J., Benham, J. L., Honarmand, K., Hu, J., Lang, R., Stelfox, H. T., & Fiest, K. (2022). Public perceptions during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada: A demographic analysis of self-reported beliefs, behaviors, and information acquisition. BMC Public Health, 22(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-13058-3

Linka, K., Rahman, P., Goriely, A., & Kuhl, E. (2020). Is it safe to lift covid-19 travel bans? the newfoundland story. Computational Mechanics, 66(5), 1081–1092. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00466-020-01899-x

Lytvyak, E., Straube, S., Modi, R., & Lee, K. K. (2022). Trends in obesity across Canada from 2005 to 2018: A consecutive cross-sectional population-based study. CMAJ Open, 10(2). https://doi.org/10.9778/cmajo.20210205

Mayo Clinic. (2024, April 30). Covid-19: Who’s at higher risk of serious symptoms? https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/coronavirus/in-depth/coronavirus-who-is-at-risk/art-20483301

Muleme, J., Kankya, C., Ssempebwa, J. C., Mazeri, S., & Muwonge, A. (2017). A framework for integrating qualitative and quantitative data in knowledge, attitude, and practice studies: A case study of pesticide usage in Eastern Uganda. Frontiers in Public Health, 5. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2017.00318

Otter.ai, Inc. (2023). Otter voice meeting notes [Computer software]. https://otter.ai/

Papagiannis, D., Malli, F., Raptis, D. G., Papathanasiou, I. V., Fradelos, E. C., Daniil, Z., Rachiotis, G., & Gourgoulianis, K. I. (2020). Assessment of knowledge, attitudes, and practices towards new coronavirus (SARS-COV-2) of health care professionals in Greece before the outbreak period. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(14), 4925. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17144925

Parsons Leigh, J., Fiest, K., Brundin-Mather, R., Plotnikoff, K., Soo, A., Sypes, E. E., Whalen-Browne, L., Ahmed, S. B., Burns, K. E., Fox-Robichaud, A., Kupsch, S., Longmore, S., Murthy, S., Niven, D. J., Rochwerg, B., & Stelfox, H. T. (2020). A national cross-sectional survey of public perceptions of the COVID-19 pandemic: Self-reported beliefs, knowledge, and behaviors. PLOS ONE, 15(10). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0241259

Public Health Agency of Canada. (2024, June 11). Covid-19 epidemiology update: Current situation. Canada.ca. https://health-infobase.canada.ca/covid-19/current-situation.html?stat=rate&measure=deaths_total&map=pt#a2

Quigley, A. L., Stone, H., Nguyen, P. Y., Chughtai, A. A., & MacIntyre, C. R. (2021). Estimating the burden of covid-19 on the Australian Healthcare Workers and Health System during the first six months of the pandemic. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 114, 103811. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103811

Renjith, V., Yesodharan, R., Noronha, J., Ladd, E., & George, A. (2021). Qualitative methods in health care research. International Journal of Preventive Medicine, 12(1), 20. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijpvm.ijpvm_321_19

Rothe, C., Schunk, M., Sothmann, P., Bretzel, G., Froeschl, G., Wallrauch, C., Zimmer, T., Thiel, V., Janke, C., Guggemos, W., Seilmaier, M., Drosten, C., Vollmar, P., Zwirglmaier, K., Zange, S., Wölfel, R., & Hoelscher, M. (2020). Transmission of 2019-ncov infection from an asymptomatic contact in Germany. New England Journal of Medicine, 382(10), 970–971. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmc2001468

Saunders, B., Sim, J., Kingstone, T., Baker, S., Waterfield, J., Bartlam, B., Burroughs, H., & Jinks, C. (2017). Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and Operationalization. Quality & Quantity, 52(4), 1893–1907. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-017-0574-8

World Health Organization. (2024). WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) dashboard > Deaths [Dashboard]. https://data.who.int/dashboards/covid19/deaths

Zhu, H., Wei, L., & Niu, P. (2020). The novel coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan, China. Global Health Research and Policy, 5(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41256-020-00135-6

SUPPLEMENTARY TABLES

| TABLE 1A: Interview guide to identify the knowledge, attitude, and practice regarding COVID-19 in NL among non-COVID-19 patients. | |

| Demographic characteristics |

1. Age 2. Gender and Sex 3. Education 4. Employment (healthcare worker, essential worker, non-essential worker, student, N/A) 5. Residence (Name of city/Town in NL) 6. Living with family members (Yes, No) 7. Do you identify with the following groups (Members of the LGBTQ+ community, Immigrants/refugees, and senior citizens)? 8. Do you identify with any race or ethnicity? |

| KAP SPECIFIC QUESTIONS | 1. Please tell me what you know about SARs-CoV-2, the virus.

2. Please tell me what you know about COVID-19, the disease. 3. Where do you get and read information about COVID-19? 4. Do you trust the information you read regarding COVID-19? Why or why not? 5. What do you think are COVID-19 symptoms? 6. How do you think COVID-19 spreads? 7. Did your behaviour/activities change during the COVID-19 pandemic? Why/Why not? 8. What do you know about the COVID-19 vaccine? 9. Did you receive the COVID-19 vaccines, including all three doses, and would you like to receive additional doses in the future? Why or why not? 10. What are your opinions regarding the NL public health measures against COVID-19? 11. Now that the provincial government has removed mask mandates, would you still wear your mask regardless? Why or why not? 12. How do you think we can improve our pandemic management strategies for any future pandemics? 13. Do you think you are at risk of getting severe COVID-19? |

| TABLE 2A: Interview guide to explore COVID-19 patient experiences in NL. | |

| Demographic characteristics

|

1. Age 2. Gender and Sex 3. Education 4. Employment (healthcare worker, essential worker, non-essential worker, student, N/A) 5. Residence (Name of city/Town in NL) 6. Living with family members (Yes, No) 7. Do you identify with the following groups (Members of the LGBTQ+ community, Immigrants/refugees, and senior citizens)? 8. Do you identify with any race or ethnicity? |

| LIVED EXPERIENCE RELATED QUESTIONS | 1. What do you know about COVID-19 before your diagnosis?

2. Why did you get tested for COVID-19? 3. Did you think you had COVID-19 before being diagnosed? 4. When you knew you had COVID-19, what was the first thing that came to mind? 5. What are your concerns and worries before and after the diagnosis? 6. After your diagnosis, can you describe the experience of one day dealing with this disease? 7. After your diagnosis, how did you get treated for COVID-19? Were you admitted to a healthcare facility or had to isolate yourself at home? 8. What was your experience with healthcare providers (doctors, nurses, etc.) for your COVID-19 diagnosis? 9. What did you think about the care and treatment you received for COVID-19? 10. How did you think your diagnosis affected the people around you, including family, friends, and the workplace? 11. What challenges did you experience with COVID-19 infection? 12. After recovering from COVID-19, have you had to change your hygiene and lifestyle? 13. How did your knowledge and opinion on COVID-19 change after this experience? 14. What are your opinions of the COVID-19 vaccines before and after the diagnosis? 15. What are your opinions of the NL public health restrictions (masks, limited in-person gatherings, etc.) before and after the diagnosis? |