Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the number and characteristics of public drug program beneficiaries in Ontario, Canada

Zachary Bouck, Daniel McCormack, Mina Tadrous, J. Michael Paterson, Tonya Campbell, Tara Gomes

ABSTRACT

Introduction: In March 2020, the provincial government of Ontario, Canada enacted emergency public health measures to limit SARS-CoV2 transmission, including non-essential service closures, which contributed to substantial job and earnings losses. Concurrently, the federal government introduced temporary income benefits for Canadians with lost earnings due to COVID-19. We evaluated the collective effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, provincial emergency measures, and temporary federal income benefits on the number of Ontarians qualifying for public prescription drug insurance as provincial social assistance recipients over time. Methods: Using administrative data from January 2019–March 2021, we conducted interrupted time series analyses of Ontario Drug Benefit (ODB) beneficiaries aged <65 years qualifying as Ontario Works (OW) or Ontario Disability Support Program (ODSP) recipients. We used segmented regression models to estimate joint effects of the COVID-19 related interventions, which were first implemented in March 2020, on the monthly number of ODB beneficiaries receiving OW or ODSP benefits. Senior ODB beneficiaries (all Ontario residents aged ≥65 years) were analyzed separately as a control series. Results: Post-implementation, the interventions were associated with an immediate absolute increase in the number of ODB beneficiaries qualifying via OW (19,025; 95% CI=9,265–28,784) and gradual absolute reductions in the number of ODB beneficiaries qualifying through OW (-5,680 per month, on average; 95% CI=[-7,857]–[-3,502]) or ODSP (-1,993 per month, on average; 95% CI=[-2,500]–[-1,486]) beyond pre-implementation trends. Overall, the interventions were associated with 49,135 fewer OW beneficiaries (95% CI=[-75,175]–[-23,095]) and 20,356 fewer ODSP beneficiaries (95% CI=[-26,821]–[-13,891]) than expected in March 2021 had the interventions not occurred. The interventions were not associated with meaningful changes in the senior (control) series. Conclusions: Despite job and wage losses due to the pandemic, we observed gradual and overall decreases in the number of ODB beneficiaries qualifying as social assistance recipients in the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, presumably due to the introduction of temporary federal income supports to help workers recover lost earnings. Further research should examine how withdrawal of federal income supports may have contributed to subsequent gaps in public drug coverage among low-income adults and families in Ontario.

Authors credentials and affiliations:

Z Bouck PhD1,2, D McCormack MSc3, M Tadrous PhD1,2,3, J M Paterson MSc 3,4,5, T Campbell MPH2, T Gomes PhD1,2,3,4

- Leslie Dan Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

- Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute of St. Michael’s Hospital, Unity Health Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

- ICES, Toronto, ON, Canada

- Institute for Health Policy, Management and Evaluation, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

- Department of Family Medicine, McMaster University, Hamilton, ON

Corresponding author: Tara Gomes [email protected] 416-864-6060 x77046 30 Bond St., Toronto, ON, Canada. M5B 1W8

Acknowledgments: This study was funded by the Ontario Ministry of Health (Grant # 0691). This study was also supported by ICES, which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health (MOH) and the Ministry of Long-Term Care (MLTC). Parts of this material are based on data and information compiled and provided by the Ontario Ministry of Health, the Ontario Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services, and the Canadian Institute for Health Information. We thank IQVIA Solutions Canada Inc. for use of their Drug Information File. This document used data adapted from the Statistics Canada Postal CodeOM Conversion File, which is based on data licensed from Canada Post Corporation, and/or data adapted from the Ontario Ministry of Health Postal Code Conversion File, which contains data copied under license from ©Canada Post Corporation and Statistics Canada. The analyses, conclusions, opinions, and statements expressed herein are solely those of the authors and do not reflect those of the funding or data sources; no endorsement is intended or should be inferred. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Data sharing statement: The dataset used in this study is held securely in coded form at ICES. While legal data sharing agreements between ICES and data providers (e.g., healthcare organizations and government) prohibit ICES from making the dataset publicly available, access may be granted to those who meet pre-specified criteria for confidential access, available at www.ices.on.ca/DAS (email: [email protected]). The full dataset creation plan and underlying analytic code are available from the authors upon request, understanding that the computer programs may rely upon coding templates or macros that are unique to ICES and are therefore either inaccessible or may require modification.

Status: Peer reviewed.

Submitted: 02 JUL 2024 | Published: 22 JUL 2024

Citation: Zachary Bouck, Daniel McCormack, Mina Tadrous, J. Michael Paterson, Tonya Campbell, Tara Gomes (2024). Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the number and characteristics of public drug program beneficiaries in Ontario, Canada. Canadian Health Policy, JUL 2024. https://doi.org/10.54194/GVUQ2702. canadianhealthpolicy.com.

INTRODUCTION

Healthcare services in Canada are largely covered through universal, tax-funded provincial and territorial public insurance plans; however, public insurance coverage for outpatient prescription medications is limited to specific populations (e.g., low-income and older adults) and many Canadians rely on private insurance and out-of-pocket payments to cover part or all of their drug expenses.1 In Ontario, Canada’s most populous province, approximately 1-in-4 residents received prescription drug coverage through the province’s main public drug plan, the Ontario Drug Benefit (ODB) program, between April 2019 and March 2020.2 In the same fiscal year (FY 2019/20), the provincial government covered 91% of prescription drug costs ($7.3 billion CAD) across 185.7 million processed claims for ODB beneficiaries, with the remaining 9% ($0.7 billion CAD) paid by recipients.2 Ontarians belonging to any of the following eligibility groups automatically qualify for ODB coverage: seniors (≥65 years old); provincial social assistance recipients; residents of long-term care homes, special care homes, or community homes for opportunity; recipients of professional home and community care programs; Trillium Drug Plan beneficiaries (high drug costs relative to income); and residents aged ≤24 years old not covered by private insurance. Nearly 70% of ODB recipients in 2019/20 were eligible beneficiaries due to being seniors or receiving provincial social assistance benefits through the Ontario Works (OW) program for lower-income adults who are out of work, or the Ontario Disability Support Program (ODSP) for people with permanent disabilities who are unable to work.3,4

On March 17th, 2020, the Government of Ontario implemented COVID-19 emergency public health measures to close non-essential services and facilitate physical distancing to reduce SARS-CoV2 transmission.5 These provincial emergency measures were associated with the largest annual loss of jobs in Ontario on record (355,300 jobs lost in 2020) and the highest unemployment rate since 1993 (9.6% in 2020), with 1-in-10 jobs experiencing a ≥50% COVID-19-related reduction in work hours.6 To help mitigate the negative economic consequences of the pandemic and provincial/territorial emergency measures, the Canadian federal government established temporary income supports from March 15th, 2020 through September 25th, 2021 for Canadians with reduced earnings due to the pandemic, which included the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB) and recovery benefits that supplanted the CERB.7 In the absence of these federal income benefits, it is reasonable to expect that pandemic-related labour market disruptions would contribute to increasing numbers of lower-income Ontarians eligible for OW or ODSP financial assistance, which automatically confers ODB coverage for recipients.8 However, it is presently understudied whether, and to what extent, the federal emergency income benefits lessened the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and associated provincial measures on the number of ODB beneficiaries qualifying through Ontario social assistance.

Therefore, in this study, we evaluate the combined effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, initial provincial emergency measures, and temporary federal income benefits on the number and characteristics of ODB beneficiaries qualifying as Ontario social assistance (OW or ODSP) recipients or as seniors during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. Since age-based ODB eligibility was unaffected by the pandemic and associated measures, senior ODB beneficiaries were included as a control series to strengthen our inferences regarding possible intervention effects (or lack thereof) on low-income ODB beneficiaries receiving social assistance.9,10

METHODS

We conducted an interrupted time series analysis of ODB beneficiaries qualifying as social assistance recipients (OW/ODSP beneficiary, their spouse, or co-habiting dependent) or seniors (Ontario residents aged ≥65 years) in Ontario, Canada between January 1st, 2019, and March 31st, 2021. We used routinely collected administrative data that were linked using encoded identifiers and analyzed at ICES. This included records from the Registered Persons Database, which contains sociodemographic information on all Ontario residents issued an Ontario Health Insurance Plan (OHIP; the province’s public health insurance plan) health card number and was used to identify Ontario residents aged ≥65 years (i.e., senior ODB beneficiaries) and the Ontario Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services’ Social Assistance database, which contains monthly records of individuals and households receiving income support payments from OW or ODSP and was used to identify social assistance recipients (further detailed below). We also used the ODB database, which captures outpatient prescription medications dispensed to ODB beneficiaries.4 Specifically, anyone that received a non-zero monthly payment from OW or ODSP for financial or employment assistance was considered an ODB beneficiary qualifying through social assistance in that same month and for all subsequent months up to the month before (1) they had two consecutive months without financial or employment assistance payments (i.e., deemed ineligible as of second month), (2) their 65th birthday (qualify as senior ODB beneficiary), or (3) the end of the study period (March 31st, 2021), whichever came first. Individuals qualifying for ODB coverage via multiple eligibility groups in a given reporting period (month or year) only counted towards one group following the hierarchy: seniors > OW > ODSP. For example, an Ontario resident aged <65 years who qualified for both OW and ODSP in the same period was considered an OW beneficiary for that period. We used the OHIP claim database to capture all physician visits, and the Canadian Institute for Health Information Discharge Abstract Database and National Ambulatory Care Reporting System to capture inpatient hospitalizations and emergency department visits, respectively. Finally, we used a number of derived cohorts created at ICES to determine diagnoses of asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), diabetes and hypertension, and used the Johns Hopkins’ Adjusted Clinical Groups® (version 10) system to describe overall patient comorbidity status (reported as the total number of Aggregated Diagnosis Groups (ADGs)). Supplemental TABLE 1 provides data sources and definitions for all measured characteristics.

Within each ODB eligibility group of interest (OW, ODSP, or seniors), we first compared beneficiary characteristics (including age, sex, diagnoses of asthma, COPD, diabetes or hypertension, number of ADGs, and health care utilization) between the first year of the pandemic (FY 2020/21) and the preceding year (FY 2019/20) using standardized differences, with absolute values ≥.10 interpreted as meaningful imbalances.11 We independently analyzed monthly data from January 2019–March 2021 on the number of ODB beneficiaries qualifying via OW, ODSP, any Ontario social assistance program (OW or ODSP), or as seniors using segmented linear regression models with autoregressive errors and terms for time (t, in months [range = 0–25]; treated as continuous), implementation (1 if March 2020 or later [post-implementation], 0 otherwise [pre-implementation]), and time since implementation (t-12 if post-implementation and 0 if pre-implementation; treated as continuous).9 From each fitted model, we report estimates of the joint immediate (post-implementation level change) and gradual (post-implementation slope change) effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, initial provincial public health measures, and temporary federal income supports—which were mutually first “implemented” in March 2020—on the number of ODB beneficiaries in that series, expressed as absolute differences with 95% confidence intervals (CI).9 Model parameters were estimated using maximum likelihood estimation. Autoregressive error processes were specified based on visual inspection of partial autocorrelation function plots.9 March 2020 was excluded from regression analyses since provincial emergency measures and federal income supports were first enacted mid-March, with initial CERB payments not occurring until April 2020.9 For each model, we additionally estimated the overall (immediate plus gradual) intervention effect on the number of ODB beneficiaries in that series in March 2021 by calculating the absolute difference in the fitted post-implementation and projected counterfactual (extrapolated from pre-pandemic trend) outcome responses for the final month of observation.9 A two-tailed p-value ≤.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were conducted in SAS v9.4 (SAS Institute Inc.; Cary, NC). This study was approved by the Unity Health Toronto Research Ethics Board (REB# 22-040). Study conduct and reporting were guided by published recommendations for interrupted time series designs.12,13

RESULTS

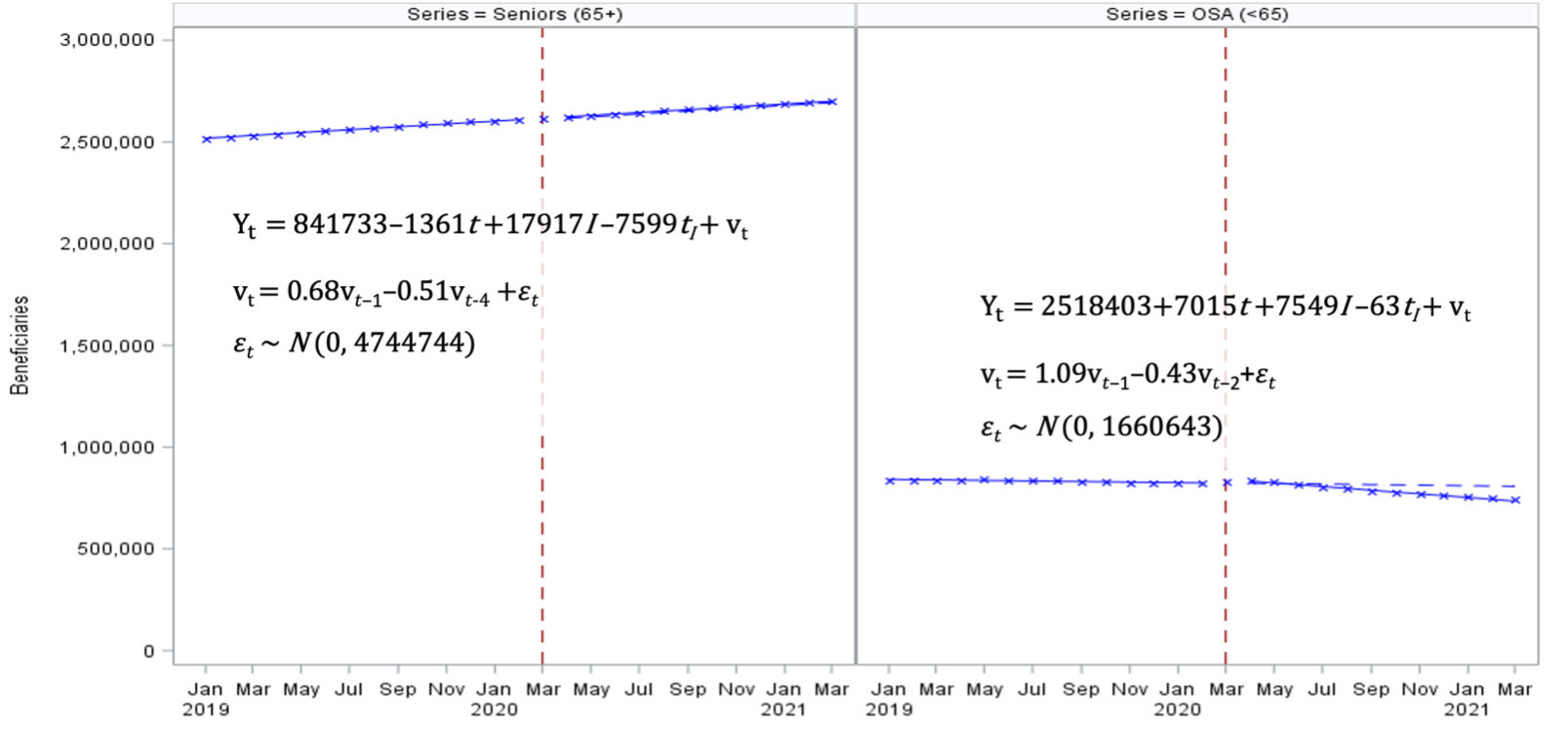

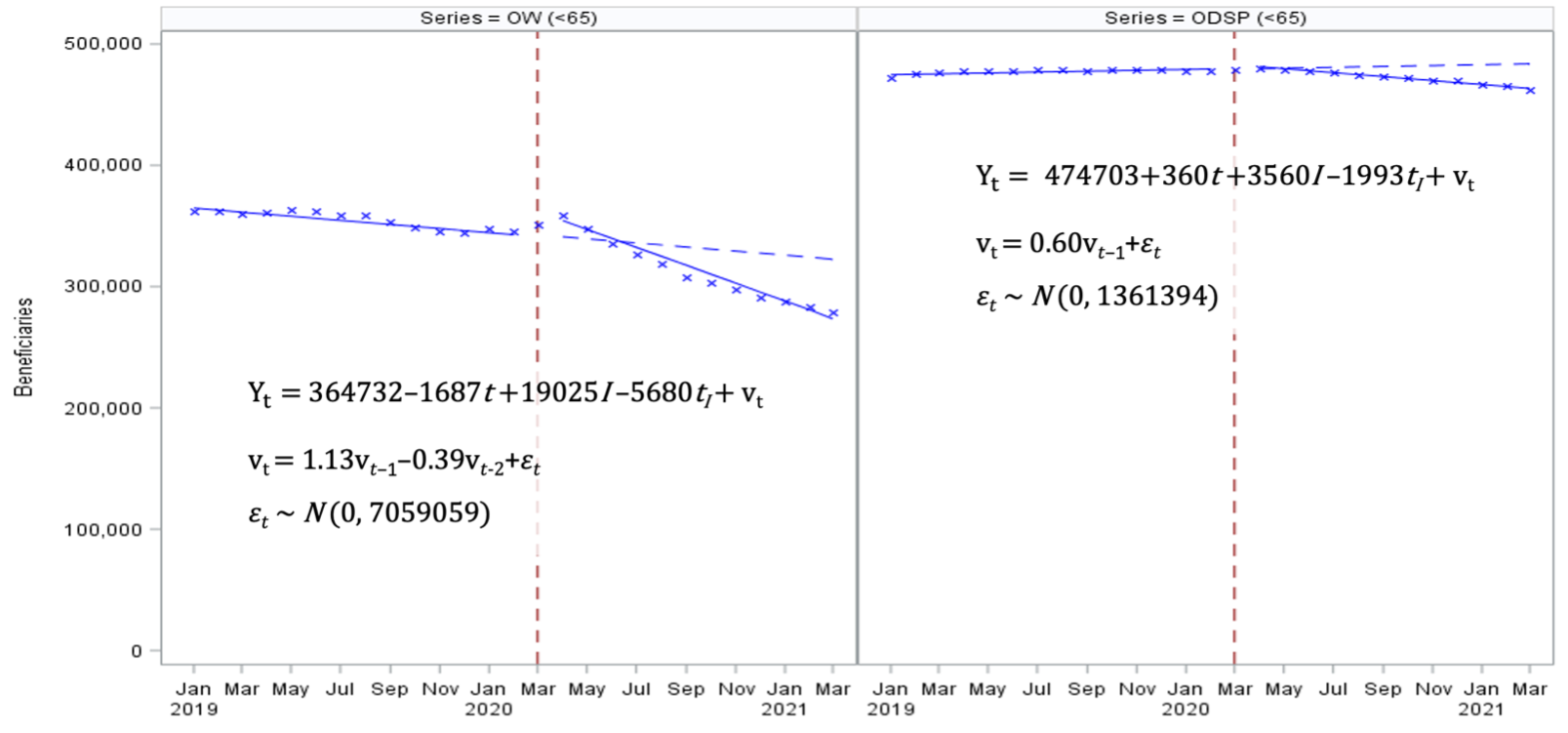

The demographic and clinical characteristics of ODB beneficiaries were largely comparable between the first year of the pandemic (FY 2020/21) and year prior (FY 2019/20), irrespective of eligibility group. However, the proportion of OW-qualifying ODB beneficiaries who received coverage for ≥1 prescription(s) was substantially lower in the first year of the pandemic compared with the preceding year (44.0% vs 50.9%; d=.14; TABLE 1). The observed average monthly number of ODB beneficiaries over our study period (January 2019–March 2021) was 2,609,580 (SD=55,799) for seniors, 335,676 (SD=28,354) for OW recipients, 475,303 (SD=4,704) for ODSP recipients, and 810,979 (SD=32,489) across both provincial social assistance programs (FIGURE 1).

According to our fitted segmented regression model, over the pre-pandemic or “pre-implementation” period (January 2019–February 2020), the number of ODB beneficiaries qualifying through Ontario social assistance declined significantly, reducing on average by 1,361 people monthly (95% CI=-1,844 to -877; p<.001). During the COVID-19 pandemic or “post-implementation” period (FY 2020/21; April 2020–March 2021), the number of ODB beneficiaries qualifying through Ontario social assistance increased significantly by 17,917 people (95% CI=11,898 to 23,936; p<.001) in the first full month of the pandemic (April 2020) versus the last pre-pandemic month (February 2020) and decreased significantly afterwards by 7,599 people per month (95% CI=-8,380 to -6,817; p<.001), on average, beyond the pre-pandemic trend. Consequently, there were an estimated 73,271 fewer ODB beneficiaries qualifying as Ontario social assistance recipients in March 2021 (95% CI=-83,105 to -63,437; p<.001) compared to the counterfactual of the pandemic and associated measures having never occurred (FIGURE 1).

FIGURE 1. Monthly number of Ontario Drug Benefit (ODB) beneficiaries, overall and by eligibility group, JAN 2019–MAR 2021.

Notes: OW = Ontario Works; ODSP = Ontario Disability Support Program; OSA = eligible for ODB coverage via OW (age<65) or ODSP (age<65). The vertical hatched red line indicates the month (March 2020) during which COVID-19 associated provincial emergency measures and temporary federal income supports were first implemented; this month was excluded from regression analyses. Observed values represented by blue circles, the solid blue lines are fitted regression trendlines for the pre-pandemic period (Jan 2019–Feb 2020) and COVID-19 pandemic period (Apr 2020–Mar 2021), and the hatched blue line represents the projected trend had the COVID-19 pandemic and associated measures not occurred (i.e., counterfactual). Fitted trendlines and counterfactuals were obtained from segmented linear autoregressive error regression models (equations overlayed in each FIGURE, where t is time in months [range = 0–25; excludes March 2020], I is a post-implementation indicator [1 if March 2020 or later, 0 if before], tI is time in months since implementation [range = 0–12]), and vt is the autoregressive error process.

Based on segmented regression analysis of the OW and ODSP series separately, over the pre-implementation period, the number of OW beneficiaries declined significantly by 1,687 people, on average, per month (95% CI=-2,764 to -610; p=.004) whereas the number of ODSP beneficiaries increased significantly by 360 people, on average, per month (95% CI=47 to 673; p=.03). Comparing April 2020 to February 2020, the number of ODB beneficiaries qualifying through OW immediately increased post-implementation by 19,025 people (95% CI=9,265 to 28,784; p<.001). While an immediate post-implementation increase of 3,560 beneficiaries (95% CI=-97 to 7,216) was also observed in the ODSP series, it was not statistically significant (p=.06). Furthermore, there were statistically significant gradual post-implementation reductions in the monthly number of ODB beneficiaries qualifying as OW recipients (5,680 fewer beneficiaries per month, on average, beyond pre-pandemic trend; 95% CI=-7,857 to -3,502; p<.001) or ODSP recipients (1,993 fewer beneficiaries per month, on average, beyond pre-pandemic trend; 95% CI=-2,500 to -1,486; p<.001). Overall, there were an estimated 49,135 fewer OW beneficiaries (95% CI=-75,175 to -23,095; p<.001) and 20,356 fewer ODSP beneficiaries (95% CI=-26,821 to -13,891; p<.001) than expected in March 2021 in the absence of the pandemic and associated measures.

Results from the senior (control) series analysis suggest an underlying positive secular trend, independent of the interventions. On average, the number of ODB beneficiaries aged ≥65 years increased significantly by 7,015 people, on average, month-to-month during the pre-intervention period (95% CI=6,498 to 7,531; p<.001). Post-implementation, the number of senior ODB beneficiaries immediately increased by 7,549 people (95% CI=1,750 to 13,347; p=.01). In comparison, the estimated post-implementation gradual decrease of 63 fewer beneficiaries per month, on average, over and above the pre-intervention trend (95% CI=-817 to 691; p=.86) was not statistically significant. Consequently, as of March 2021, the interventions were not associated with an overall change in the number of senior ODB beneficiaries (6,793 additional beneficiaries; 95% CI=-3,825 to 17,411; p=.20).

CONCLUSIONS

This study evaluated the collective short-term effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, initial provincial public health measures, and temporary federal income supports—collectively, the “interventions”, which were considered co-implemented in March 2020—on the number and characteristics of ODB beneficiaries in Ontario, Canada qualifying as provincial social assistance recipients. We observed significant post-implementation gradual and overall (as of March 2021) declines, beyond pre-pandemic trends and projections, in the monthly number of ODB beneficiaries qualifying through either provincial social assistance program, with more substantial declines observed among OW versus ODSP recipients in stratified analyses. In contrast, we observed an underlying positive secular trend in the number of ODB beneficiaries qualifying as seniors throughout the study period (presumably due to aging of the Ontario population), with no discernable difference between the pre- and post-implementation trends to suggest gradual or overall intervention effects. These findings fit with our expectations for this control series, since the pandemic and associated measures did not affect age-based eligibility for ODB coverage.

Observed declines in the number of Ontario social assistance recipients during the first year of the pandemic fit with prior investigations. First, a report using annual (fiscal year average) data from the provincial government found an absolute decrease of 40,996 OW beneficiaries (9.3% relative reduction) from FY 2019/20 to FY 2020/21, which represents the largest year-over-year drop for this program in the past 20 years.14 For comparison, the number of ODSP beneficiaries modestly declined by 1,530 people (0.3% relative reduction) between FY 2019/20 and FY2020/21.14 Second, a study using monthly social assistance data from April–October 2020 observed a steady, gradual decline in the OW caseload, with a 15% relative reduction in the number of single adults or families receiving OW benefits between April and September 2020; the ODSP caseload decreased by less than 2% over the same period.7 Our study builds upon these earlier descriptive studies through analysis of monthly data to quantify the joint immediate, gradual, and overall effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, provincial public health measures, and temporary federal income supports on the number of ODB beneficiaries qualifying as social assistance recipients, while offering a more comprehensive summary of beneficiary composition in the immediate pre-pandemic and pandemic periods.7,14

In agreement with these earlier investigations, we caution against attributing the observed gradual and overall declines in ODB beneficiaries qualifying as OW or ODSP recipients to meaningful reductions in unemployment and poverty in Ontario during the first year of the pandemic.7,14 These declines are more likely owed, in part, to many Ontarians receiving federal COVID-19 emergency income supports, including the CERB, which may have resulted in reductions in successful OW/ODSP applications and retention of existing OW/ODSP clients.7,14 In particular, the Government of Ontario announced that new applicants to OW (applied on or after March 1st, 2020) would have the full amount of any received federal emergency payments count towards their qualifying income, which could have disqualified some applicants (including single adults without dependents) from program entry and disincentivized others from applying.7,14 This may partially explain the more rapid declines observed in the number of OW- versus ODSP-qualifying ODB beneficiaries during the first year of the pandemic. For existing OW recipients (applied before March 1st, 2020), existing ODSP clients, and ODSP applicants, the Government of Ontario announced that any income received via temporary federal emergency supports would only count partially towards their qualifying income; however, if these individuals’ qualifying income exceeded the corresponding programs’ maximum threshold (dependent on benefit unit type and size), these beneficiaries would receive nominal financial assistance payments via OW or ODSP to ensure continued access to other program benefits, including ODB coverage.7 Despite this, receipt of only nominal income assistance payments for existing OW and ODSP clients currently receiving federal income supports may have contributed to reduced retention in these programs over time, particularly for OW where income assistance is intended to be of shorter duration compared to ODSP.7,14

Though our study has several strengths, including analysis of a concurrent control series, there are limitations worth noting. Due to their concurrent implementation, we were unable to disentangle and compare the effects of each component intervention (e.g., provincial public health measures) on observed trends in low-income ODB beneficiaries.9 Furthermore, without data on which participants received temporary federal income support payments and the subset who unsuccessfully applied for social assistance over the study period, we cannot assert whether observed declines in OW/ODSP recipients were primarily driven by reduced entries into, versus increased exits from, these provincial programs during the pandemic period.

Despite these limitations, our results suggest that the availability of temporary federal income supports—which were intended to mitigate lost earnings due to COVID-19—in combination with changes to program eligibility were associated with a reduction in Ontario social assistance recipients (particularly for OW) over the first year of the pandemic, resulting in fewer Ontarians qualifying for public drug plan coverage through social assistance over this period.7,14 Further research should examine whether, and to what extent, the availability and withdrawal of COVID-19-related federal income benefits contributed to short- and long-term gaps in ODB prescription drug coverage among low-income adults and families in Ontario, with emphasis on those who do not belong to any other ODB eligibility groups.

REFERENCES

- Brandt J, Shearer B, Morgan SG. Prescription drug coverage in Canada: a review of the economic, policy and political considerations for universal pharmacare. J of Pharm Policy and Pract. 2018 Dec;11(1):28.

- OPDP At A Glance: Fiscal Year 2019/20 Snapshot Report. Available from: https://www.ontario.ca/page/ontario-public-drug-programs/

- Government of Ontario M of H and LTC. Executive Officer Communications – Ontario Public Drug Programs – Health Care Professionals – MOHLTC [Internet]. Government of Ontario, Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care; [cited 2023 Aug 29]. Available from: https://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/drugs/publications/opdpataglance/

- de Oliveira C, Gatov E, Rosella L, Chen S, Strauss R, Azimaee M, et al. Describing the linkage between administrative social assistance and health care databases in Ontario, Canada. Int J Popul Data Sci. 7(1):1689.

- Ontario Agency for Health Protection and Promotion (Public Health Ontario). Trends of COVID-19 incidence in Ontario [Internet]. 2021. Available from: https://www.publichealthontario.ca/-/media/documents/ncov/epi/covid-19-epi-trends-incidence-ontario.pdf?la=en

- https://www.fao-on.org. Ontario’s Labour Market in 2020 [Internet]. Financial Accountability Office of Ontario (FAO). [cited 2023 Nov 15]. Available from: https://www.fao-on.org/en/Blog/Publications/labour-market-2021

- Petit G, Tedds LM. Interactions between Federal and Provincial Cash Transfer Programs: The Effect of the Canada Emergency Response Benefit on Provincial Income Assistance Eligibility and Benefits. SSRN Journal [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2023 Sep 20]; Available from: https://www.ssrn.com/abstract=3850825

- Get coverage for prescription drugs | ontario.ca [Internet]. [cited 2023 Nov 17]. Available from: http://www.ontario.ca/page/get-coverage-prescription-drugs

- Wagner AK, Soumerai SB, Zhang F, Ross-Degnan D. Segmented regression analysis of interrupted time series studies in medication use research. Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics. 2002;27(4):299–309.

- Lopez Bernal J, Cummins S, Gasparrini A. Interrupted time series regression for the evaluation of public health interventions: a tutorial. Int J Epidemiol. 2016 Jun 9;dyw098.

- Mamdani M, Sykora K, Li P, Normand SLT, Streiner DL, Austin PC, et al. Reader’s guide to critical appraisal of cohort studies: 2. Assessing potential for confounding. BMJ. 2005 Apr 23;330(7497):960–2.

- Ramsay CR, Matowe L, Grilli R, Grimshaw JM, Thomas RE. Interrupted time series designs in health technology assessment: Lessons from two systematic reviews of behavior change strategies. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2003 Dec;19(4):613–23.

- Turner SL, Karahalios A, Forbes AB, Taljaard M, Grimshaw JM, Cheng AC, et al. Design characteristics and statistical methods used in interrupted time series studies evaluating public health interventions: a review. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2020 Jun;122:1–11.

- Tabbara M. Social Assistance Summaries, 2021. July 2022. Available from: https://maytree.com/wp-content/uploads/Social_Assistance_Summaries_2021.pdf

TABLES

| TABLE 1. Ontario Drug Benefit (ODB) beneficiary characteristics before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in Ontario, Canada by eligibility group, April 2019–March 2021. | |||||||||

| Beneficiary characteristics | Ontario Works (<65) | Ontario Disability Support Program (<65) | Seniors (65+) | ||||||

| Pre-COVID-19

(FY 2019/20) N = 486,150 |

During COVID-19

(FY 2020/21) N = 414,055 |

d | Pre-COVID-19

(FY 2019/20) N = 518,552 |

During COVID-19

(FY 2020/21) N = 508,275 |

d | Pre-COVID-19

(FY 2019/20) N = 2,712,425 |

During COVID-19

(FY 2020/21) N = 2,797,857 |

d | |

| ODB recipientsa, n (%) | 247,384 (50.9) | 182,241 (44.0) | .14 | 406,158 (78.3) | 377,644 (74.3) | .09 | 2,402,210 (88.6) | 2,430,657 (86.9) | .05 |

| Drug costs to government payer | |||||||||

| Total in CAD millions (M) | $197.3 M | $168.8 M | – | $1,123.2 M | $1,105.2 M | – | $4,266.1 M | $4,559.5 M | – |

| Average per claimant in CAD | $797.37 | $925.99 | – | $2,765.45 | $2,926.43 | – | $1,775.90 | $1,875.80 | – |

| Age (in years), mean (SD) | 25.5 (17.6) | 25.5 (17.8) | .00 | 38.3 (17.9) | 38.4 (17.9) | .01 | 74.2 (7.8) | 74.2 (7.8) | .00 |

| Age group (in years), n (%) | |||||||||

| <15 | 165,806 (34.1) | 143,976 (34.8) | .01 | 64,904 (12.5) | 63,422 (12.5) | .00 | N/A | N/A | – |

| 15-24 | 74,935 (15.4) | 61,454 (14.8) | .02 | 71,241 (13.7) | 67,517 (13.3) | .01 | N/A | N/A | – |

| 25-34 | 91,775 (18.9) | 75,685 (18.3) | .02 | 75,698 (14.6) | 75,739 (14.9) | .01 | N/A | N/A | – |

| 35-44 | 70,261 (14.5) | 60,336 (14.6) | .00 | 76,445 (14.7) | 76,191 (15.0) | .01 | N/A | N/A | – |

| 45-54 | 49,235 (10.1) | 42,012 (10.1) | .00 | 101,960 (19.7) | 96,760 (19.0) | .02 | N/A | N/A | – |

| 55-64 | 34,138 (7.0) | 30,592 (7.4) | .01 | 128,304 (24.7) | 128,646 (25.3) | .01 | N/A | N/A | – |

| 65-74 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1,606,105 (59.2) | 1,660,089 (59.3) | .00 |

| 75-84 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 766,853 (28.3) | 790,601 (28.3) | .00 |

| ≥85 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 339,467 (12.5) | 347,167 (12.4) | .00 |

| Male, n (%b) | 235,394 (48.4) | 198,256 (48.0) | .01 | 269,169 (51.9) | 263,846 (51.9) | .00 | 1,241,757 (45.8%) | 1,282,182 (45.8) | .00 |

| Neighbourhood income quintile, n (%) | |||||||||

| 1 (lowest) | 230,594 (47.4) | 197,565 (47.7) | .01 | 227,528 (43.9) | 220,491 (43.4) | .01 | 537,353 (19.8) | 547,797 (19.6) | .01 |

| 2 | 108,775 (22.4) | 92,201 (22.3) | .00 | 116,127 (22.4) | 113,915 (22.4) | .00 | 561,695 (20.7) | 575,980 (20.6) | .00 |

| 3 | 69,275 (14.2) | 58,236 (14.1) | .01 | 77,402 (14.9) | 76,411 (15.0) | .00 | 541,317 (20.0) | 559,354 (20.0) | .00 |

| 4 | 43,155 (8.9) | 36,675 (8.9) | .00 | 53,647 (10.3) | 53,504 (10.5) | .01 | 516,168 (19.0) | 536,616 (19.2) | .00 |

| 5 (highest) | 27,648 (5.7) | 23,654 (5.7) | .00 | 39,030 (7.5) | 39,144 (7.7) | .01 | 548,448 (20.2) | 570,263 (20.4) | .00 |

| Missing | 6,703 (1.4) | 5,724 (1.4) | .00 | 4,818 (0.9) | 4,810 (0.9) | .00 | 7,444 (0.3) | 7,847 (0.3) | .00 |

| Location of residence, n (%) | |||||||||

| Rural | 33,881 (7.0) | 28,619 (6.9) | .00 | 59,536 (11.5) | 58,347 (11.5) | .00 | 342,371 (12.6) | 354,207 (12.7) | .00 |

| Urban | 445,665 (91.7) | 379,787 (91.7) | .00 | 454,452 (87.6) | 445,361 (87.6) | .00 | 2,363,538 (87.1) | 2,436,797 (87.1) | .00 |

| Missing | 6,604 (1.4) | 5,649 (1.4) | .00 | 4,564 (0.9) | 4,567 (0.9) | .00 | 6,516 (0.2) | 6,853 (0.2) | .00 |

| Comorbidities (# of ADG)b, n (%) | |||||||||

| 0 to 5 | 320,992 (66.0) | 273,054 (65.9) | .00 | 259,709 (50.1) | 259,934 (51.1) | .02 | 1,043,310 (38.5) | 1,092,444 (39.0) | .01 |

| 6 to 9 | 120,380 (24.8) | 102,906 (24.9) | .00 | 155,419 (30.0) | 150,334 (29.6) | .01 | 973,315 (35.9) | 1,001,822 (35.8) | .00 |

| ≥10 | 44,778 (9.2) | 38,095 (9.2) | .00 | 103,424 (19.9) | 98,007 (19.3) | .02 | 695,800 (25.7) | 703,591 (25.1) | .01 |

| Asthma, n (%) | 76,117 (15.7%) | 64,815 (15.7%) | .00 | 123,442 (23.8) | 121,572 (23.9) | .00 | 362,935 (13.4) | 378,018 (13.5) | .00 |

| COPD, n (%) | 12,539 (2.6%) | 10,777 (2.6%) | .00 | 65,369 (12.6) | 63,539 (12.5) | .00 | 540,364 (19.9) | 553,901 (19.8) | .00 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 22,095 (4.5%) | 20,236 (4.9%) | .02 | 84,506 (16.3) | 84,637 (16.7) | .01 | 794,548 (29.3) | 826,042 (29.5) | .01 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 29,530 (6.1%) | 26,125 (6.3%) | .01 | 106,687 (20.6) | 103,855 (20.4) | .00 | 1,803,963 (66.5) | 1,846,626 (66.0) | .01 |

| Physician visits in past year, mean (SD) | 9.1 (17.0) | 9.2 (17.2) | .01 | 15.9 (26.8) | 15.6 (26.8) | .01 | 15.2 (20.1) | 14.9 (20.0) | .02 |

| ED visit in past year, n (%) | 161,756 (33.3) | 135,426 (32.7) | .01 | 198,868 (38.4) | 190,793 (37.5) | .02 | 742,576 (27.4) | 743,448 (26.6) | .02 |

| Hospitalization in past year, n (%) | 41,220 (8.5) | 33,985 (8.2) | .01 | 47,032 (9.1) | 44,656 (8.8) | .01 | 281,208 (10.4) | 280,033 (10.0) | .01 |

| Notes: FY = fiscal year (Apr–Mar of next year); d = absolute standardized (mean or %) difference; SD = standard deviation; ADG = Johns Hopkins’ Aggregated Diagnostic Groups® (version 10); COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ED = emergency department; % = column percentages. Characteristics for a given individual assessed on their 1st day of ODB eligibility in FY (index date). a Received ODB coverage for ≥1 prescription drugs in FY (may be alternatively referred to as a “utilizing beneficiary” or “claimant”). b Based on past 2 years. | |||||||||

Supplemental TABLE 1. Measured beneficiary characteristics with corresponding data sources and definitions.

| Characteristic | Data sources | Definition/coding |

| Ontario Drug Benefit (ODB) recipient | ODB database | Any dispensation in past year (365 days) before index date. in ODB. |

| Age | Registered Persons Database (RPDB) | Age in years on index date. |

| Sex | RPDB | Male or female (sex at birth) |

| Neighbourhood income quintile | RPDB | Derived using Statistic Canada’s Postal Code Conversion File; based on postal code in RPDB |

| Location of residence | RPDB | Rural, urban, or missing |

| Asthma | ICES’ ASTHMA database | Any prior diagnosis using validated definition |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) | ICES’ COPD database | Any prior diagnosis using validated definition |

| Diabetes | Ontario Diabetes Database [ODD] | Any prior diagnosis using validated definition |

| Hypertension | ICES’ HYPER database | Any diagnosis using validated algorithm. |

| Number of comorbidities (# of ADG groups) | Discharge Abstract Database (DAD), Ontario Health Insurance Plan (OHIP) database, and Same Day Surgery (SDS) | Using claims from past 2 years, identified # of Aggregated Diagnostic Groups (ADGs) derived from Johns Hopkins’ Adjusted Clinical Groups® (version 10) system. |

| Physician visits in past year | OHIP | Counted all unique outpatient physician visits in past year (365 days) before index date, restricting to a maximum of one visit per unique physician per day. |

| Emergency department (ED) visit in past year | National Ambulatory Care Reporting System (NARCS) database | At least one ED visit in past year (365 days) before index date. |

| Hospitalization in past year | DAD | At least one inpatient hospitalization in past year (365 days) before index date. |

Note: All characteristics measured for anyone identified as an ODB beneficiary in a given fiscal year (FY 2019/20 or FY 2020/21; see TABLE 1). If a beneficiary was eligible for ODB before first date of FY, then their characteristics were assessed on first day (April 1st) of that FY (index date); otherwise, if an individual became ODB eligible during a given year, then their characteristics were measured on their first date of eligibility in the same year (index date).