Exploring the Ethics of Paediatric Surgical Prioritization in Canada: A Survey of Existing Institutional Guidance

Kayla Wiebe, Randi Zlotnik Shaul, Simon Kelley, Roxanne Kirsch

ABSTRACT

It is widely understood that surgical waitlists were globally exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Canada is no exception, and the paediatric surgical backlogs pose especially pressing problems in this particularly underserved population. While sustained ethical attention in these areas alone is not sufficient to resolve the surgical backlog problem, it is imperative for ongoing solutions. At our institution, we developed an ethics framework specifically for the context of surgical resource allocation and prioritization, and we sought to understand if other paediatric centres across Canada had done the same. We reached out to paediatric hospitals with surgical programs across Canada and received three other ethics-related guidance documents specific to or inclusive of the context of resource allocation in non-critical care contexts, such as surgery. While we found wide consensus between ethics principles in the documents we received, the paucity of guidance is notable. Surgical resource allocation and prioritization, like many contexts of ‘normal’ resource allocation, continues to lack the sustained ethical attention that could be part of ongoing solutions. Attention has focused, understandably, on clearing surgical backlogs as effectively as possible. While this is crucial, these decisions are value laden, and warrant explicit ethical attention.

Authors: Kayla Wiebe MA PhD candidate,1 Randi Zlotnik Shaul PhD,1 Simon Kelley MBChB PhD,2 Roxanne Kirsch MD1, 3

- Department of Bioethics, The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto

- Orthopedic Surgery, Department of Surgery, The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto

- Department of Critical Care Medicine, The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto

Correspondence: Kayla Wiebe, [email protected]

Disclosure: no conflicts declared.

Status: Peer reviewed.

Submitted: 02 JUL 2024 | Published: 29 JUL 2024

Citation: Kayla Wiebe, Randi Zlotnik Shaul, Simon Kelley, Roxanne Kirsch (2024). Exploring the Ethics of Paediatric Surgical Prioritization in Canada: A Survey of Existing Institutional Guidance. Canadian Health Policy, JUL 2024. https://doi.org/10.54194/OUQU6069 canadianhealthpolicy.com.

INTRODUCTION

It is fairly common for the discourse (both public and academic) about the ethics of resource allocation to spike around emergencies, to wane as things become less obviously urgent, and for that discourse to center around “extreme and tragic situations of shortage” (Ravitsky, 2022, 484). To quote directly from Hastings Center President, Dr. Vardit Ravitsky, particularly the latter tendency can “reinforce the illusion that for the rest of the time, outside the ICU, or in non-pandemic circumstances, there is no need to worry” (Ravitsky, 2022, 484). One encouraging consequence of this most recent pandemic has been calls to direct explicit attention to the ethics of resource allocation outside of the ICU, and beyond the context of imminent disaster (Garrett et al., 2020, Ravitsky, 2022). One way in which ‘explicit attention’ to the ethics of normal resource allocation is lacking is that there is a dearth of practical guidance for resource allocation and priority-setting decision-making in a variety of ‘normal’ contexts of resource constraint. This absence is particularly notable when considering the practical guidance for resource allocation and priority-setting in acute contexts, such as for allocating scarce critical care resources during the COVID-19 pandemic (Truog et al., 2020; Valiani et al., 2020; White & Lo, 2021; Downar et al., 2022).

The focus of our work has been on one particular context of normal resource allocation: surgical waitlists. Despite the recognition that the surgical backlogs across the globe constitute a serious problem, understanding surgical resource allocation and prioritization as a value laden activity, rather than an administrative, purely procedural one, is relatively novel (Kelly et al., 2022). For the most part, distinctly ethical lenses have not been brought to these domains to guide practice, in the form of things like ethics frameworks, policies, or guidelines that are suited to particular contexts.

Exceptions to this claim, of course, include published works citing this as a phenomenon in the first place (Wiebe et al., 2021; Kelly et al., 2022). One notable practical exception to this is New Zealand’s recently proposed surgical ‘equity-adjustor,’ which considers ethnicity as a factor in surgical prioritization. The equity-adjustor adds priority for Māori and Pacific Islander patients (Faa, 2023), in explicit recognition that these patients experience well-documented health inequities, such as disproportionately longer wait-times and higher risk of post-operative mortality, and the fact that these disparities are prevalent even in elective, and not just acute, surgery (Ronald et al., 2023, 2567). This is an example of precisely the kind of explicit attention and ethically informed practical guidance that a ‘normal’ context like surgical prioritization deserves. Exceptions aside, taking an explicitly ethical approach to inform practical guidance in these resource allocation contexts is still relatively new and not widespread. Further, there is a dearth of Canadian-specific guidance related to the ethical dimensions of resource allocation and prioritization guidance in this context as well. Guidance dwindles even further when focus is narrowed to paediatrics, which is unique enough to warrant distinct consideration.

Recognition that surgical prioritization and resource allocation present problems for healthcare systems is growing, and it would be difficult to find someone who objected to the claim that these issues are also ethically laden. However, as stated above, it is relatively novel to frame surgical resource allocation and prioritization within institutions as endeavours that warrant explicit ethical attention. Given the unique context of paediatric surgical delivery in Canada, developing approaches that attend to those realities is imperative (Skarskgard, 2020). The surgical backlog problem in Canada has reflected insufficient funding and resource management for a prolonged period, with paediatric care particularly underserved. Recognizing a need for sustained ethical attention to ‘normal’ contexts of resource constraint beyond triage (Garrett et al., 2020), and following a directive from Ontario Health (Ontario Health, 2020), our institution developed an Ethics Framework for the Allocation of Operative Time in 2020 (Wiebe et al., 2023).

After this, we sought to understand how other Canadian paediatric centres and institutions were addressing the ethical dimensions of surgical resource allocation and prioritization in the wake of the pandemic. Our search revealed that there are very few ethics-related materials (e.g., frameworks, policies, or guidelines) to guide practice that are specific to the surgical context. The tools that do exist focus on classifying degrees of urgency of surgical cases, reflecting an approach to prioritization based primarily on ‘urgency.’ Importantly, this does not address the ethical dimensions of this approach, such as how to balance the consequences to non-urgent patients left to wait for much longer than they should.

Below we briefly explain the current state of Canadian paediatric surgical backlogs as of Spring 2024 and identify current approaches to paediatric surgical prioritization. Both help to situate the target of analysis: ethics materials related to surgical resource allocation and prioritization.

DISCUSSION

Canadian Paediatric Surgical Backlogs: Where Are We?

The impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on Canada’s surgical waitlists have been devastating and persistent (Glauser, 2020; Shapiro et al., 2022), with delays in paediatrics being particularly troubling. As of October 2023, around 17,000 Ontario children are “languishing” on waitlists (Ogilvie, 2023), 6,500 of them at SickKids alone, with 7,000 waiting in B.C (Weeks, 2023). Prior to the pandemic, only around 65% of children received surgery within their target window, suggesting longstanding insufficient resources and surgical capacity (Skarsgard, 2020). The problem has not been resolved by a return to pre-pandemic capacity: although the same number of surgeries were completed in 2021 as in 2019, the waitlist at SickKids still grew by 12% (Ogilvie, 2022).

The consequences of delay in paediatric surgery are unique due to its highly time-sensitive nature. Surgery may be timed to coincide with developmental milestones with delays potentially reducing the possibility of an optimal outcome or increase the need for additional interventions. Disease progression while awaiting surgery can be more severe, and lead to an increase in surgical complexity and complications, and in addition pose particular burdens of suffering, anxiety, uncertainty, and distress on caregivers during vulnerable social and developmental stages during a child and family’s life (Szynkaruk et al., 2014). Excessive delays can even lead to a change in surgical plan where a more complex procedure is necessary than the one originally scheduled. Delays thus pose an incredible strain on healthcare resources (Conference Board of Canada, 2023, pg. 8). The Conference Board of Canada estimated the cost of the current delays for paediatric scoliosis surgery (around 2,778 patients) alone to be 44.6 million, with an additional 1.4 million cost to the economy due to caregiver responsibility (2023, 2).

Surgical Prioritization

Our focus in this policy analysis is specifically on the ethics of surgical prioritization in a paediatric context; importantly, our claim is not that no guidance at all exist for resource allocation and prioritization in normal contexts. To this end, it is important to acknowledge a tool that is commonly used at our institution, and in the Canadian context in general, to categorize paediatric surgical cases according to level of urgency: The Paediatric Canadian Access Targets for Surgery (P-CATS) (Wright et al., 2011). The P-CATS is a national consensus tool that classifies surgical access target times according to diagnosis, occasionally further subclassified by age. Surgical priorities are structured from the most urgent (P-CATS I, with procedures performed within 24 hours) to the least urgent (P-CATS VI procedures should be performed within 12 months). In addition to setting benchmarks for surgical wait times, compliance with P-CATS has been used as a metric to assess where current waitlists stand, and specifically to identify where departures from P-CATS recommended window of time means that case is now “out of window.” While this tool exists, use is not mandated, and whether or how consistently it is used in prioritization practices across institutions is variable according to province (Arulanandam et al., 2021). Irrespective of which tool is used to determine category of urgency, it is widely understood that urgency is the primary consideration in prioritization decisions: the highest priority goes to the most urgent cases.

Finally, surgery in Canada is typically not centralized, although there are a few specialty-specific exceptions, none of which are paediatric in focus. The difference this makes to how resources are allocated, and waitlists are organized is that hospitals and surgeon groups tend to function independently and in silos, with individual surgeons are often tasked with prioritizing their own individual lists (Shapiro et al., 2022). Further, funding models like fee-for-service promote competition, act as an incentive to acquire patients, complete one’s own surgical list, and advocate for one’s own patients (Rahimi et al., 2018), a drive that turned into a near and understandable “gold-rush mentality” both throughout and coming out of the pandemic (Jain et al., 2020, pg. 4).

The situation of surgical delivery in Canada has been described by Dr. David Urbach the functional equivalent of “hundreds or thousands of surgeons operating their own private business, managing their own waitlist of patients” (Lindsay & Barak, 2023). Importantly, this structure favours competition rather than collaboration and resource sharing, which falls short of an equitable and maximally effective response to patient need. There are also upstream equity-based problems that fall to practitioners when surgery is delivered in this way: in non-centralized surgical delivery, patients are referred to individual surgeons for surgery by other providers. A 2022 cross-sectional study found that female surgeons receive less referrals than male surgeons, and that the referral pattern from male physicians in particular favours male surgeons, a pattern that does not change even when more women enter surgical disciplines (Dossa et al., 2022). A further equity consideration concerns the patients who, for reasons beyond their control, have difficulty reaching specialized care in the first place.

The burdens of the pandemic on surgical backlogs have resulted in calls to action to centralize, and initiatives to trial centralization where it is possible are underway (Ontario Health, 2023). Resolving the waitlists is a multifaceted problem, and while explicit ethical attention to these issues will not alone reduce the backlogs, it must be part of ongoing efforts to do so. We will now turn to our exploration of the existing ethics materials related to ‘normal’ resource allocation and prioritization contexts like surgery in Canada.

Ethics of Surgical Resource Allocation and Prioritization

Exploring the Landscape

After developing an Ethics Framework that contains ethical support for surgical prioritization (Wiebe et al., 2023), we sought to understand whether other paediatric centres across Canada had done the same. We already had access to ethics-related documents (guidelines, frameworks) from three other Ontario centres through a meeting of provincial partners to discuss the paediatric surgical backlog. Each of these documents provided guidance for surgical prioritization: two were specific to the context of surgical resource allocation and prioritization, while two focused on normal ‘clinical activities’ more broadly, which is inclusive of surgical resource allocation and surgical prioritization. Importantly, our centre was the only exclusively paediatric centre, as the other three provide both adult and paediatric services.

To survey the national paediatric landscape, we cast a wider net. We contacted surgical chiefs from all paediatric hospital surgical programs in Canada via email to inquire as to whether each institution had developed any ethics related material specific to the context of surgical resource allocation and prioritization. Through several rounds of email follow-ups, we received answers from four centres, each of whom stated that their centres had not developed such materials. We received no replies from the remaining centres. During the inquiry process, however, multiple centres did confirm that they had guidance for prioritization based on urgency. For some this was following P-CATS, while others had different ways of classifying degrees of urgency.

Following several rounds of email inquiries, we completed a general search for available online materials from paediatric hospitals that had surgical programs. All centres had an ethics service (one or more of: bioethics department, embedded ethicist(s), or ethics consult service), and many had publicly available ethics-related materials for clinical ethics contexts (e.g., decision-making supports), while fewer had the same materials for resource allocation and prioritization contexts. To the latter, both Alberta Health Services (AHS) and Saskatchewan Health Authority (SHA) developed resource allocation frameworks for the context of triaging scarce critical care resources (Valiani et al., 2020). Because these were specific to the context of acute scarcity, and not specific to the context of managing ‘normal’ resource allocation and prioritization (such as the surgical backlog), we did not include them in this analysis.

Comparative Analysis on Ethics Related Documents

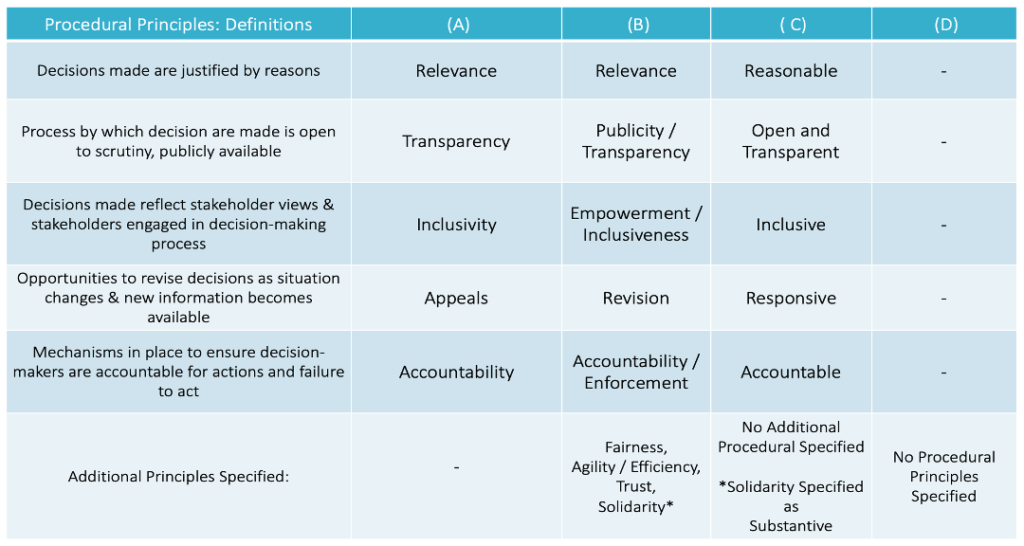

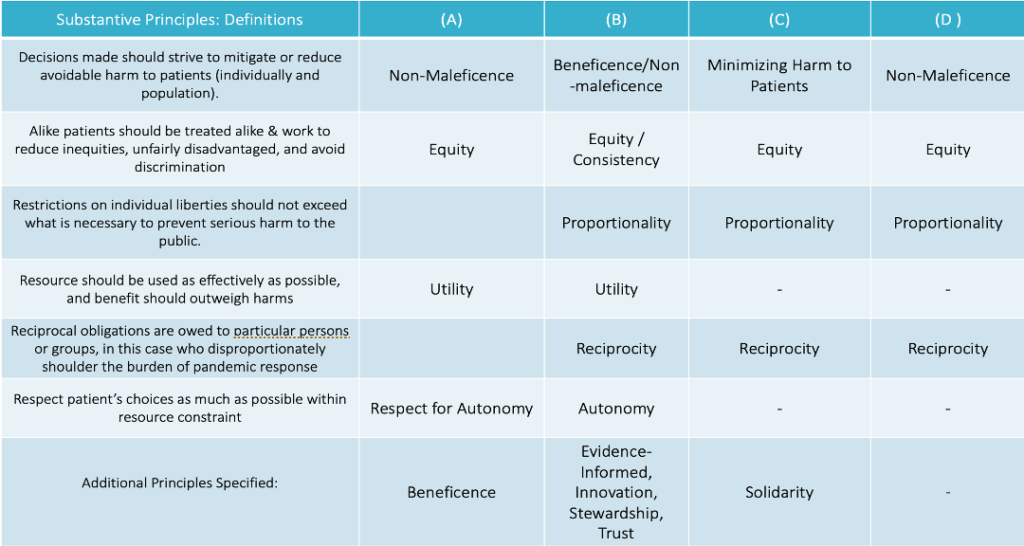

We then did a comparative analysis on the four provincial documents that we had at the outset, represented in Table 1 and 2. The institutions are referred to as A, B, C, and D, and the ethics-related document provided by each is referred to by the same letter. That is, the document produced by ‘institution A’ will also be referred to as ‘document A’, the document produced by ‘institution B’ will be referred to as ‘document B,’ and so forth. Our own institution’s Ethics Framework is published (Wiebe et al., 2023), and we therefore identify it as A. The documents provided by institutions A, B, and C were Ethics Frameworks specifically to support surgical services in and out of various levels of resource constraint, and the document provided by institution D’s was a guidance document. Each document contained ethics principles: A, B, and C contained both procedural and substantive principles, while D contained only substantive principles. Table 1 contains the procedural ethics principles, while Table 2 shows the substantive ethics principles.

In both tables, principles that were shared by two or more institutions are given their own row, while any principles that were included in only one institution’s ethics related materials are listed in the bottom row, under “Additional Principles Specified.” Given that each document contained their own distinct definition of each principle, the definitions included in the the first row of each table are general formulations of the principles as they stand in the literature. The document from A, B, C, and D each included additional ‘tools’ to assist priority setting among patients, thereby working towards operationalizing the ethical guidance set out in the documents. There were small differences regarding how different centres understood a principle as being classified as procedural or substantive. For example, B included ‘solidarity’ as a procedural principle, while D understood ‘solidarity’ as substantive. Even where there were definitional or categorical differences in how each document carved out the principles, these differences reflect similarities in substantive content. For example, while B, C, and D included proportionality as its own principle, distinct from respect for autonomy, A’s definition of respect for autonomy, built proportionality into the definition of respect for autonomy: that “any justifiable limits to autonomy should be proportional to the limits on resources available, and patient autonomy ought to be respected wherever possible” (Wiebe et al., 2023, p. 14). Further, while A included beneficence and non-maleficence as distinct principles, B counted them as one. In another case, B split efficiency from utility, while A understood utility to include a norm of efficiency. The point is that even given prima facie differences, there was wide consensus in ethics principles in this resource allocation and prioritization context. Finally, there was complete consensus on the importance of including equity and non-maleficence.

The only centres from which we have developed materials related to the ethical dimensions of surgical prioritization were from Ontario. From a policy perspective, there is a potentially interesting explanation for this outcome: in May of 2020, Ontario Health released an directive entitled “A Measured Approach to Planning for Surgeries and Procedures During the COVID-19 Pandemic” (Ontario Health, 2020). This included explicitly identified ethical principles: proportionality, non-maleficence, equity, and reciprocity. Speaking for our own institution, the development of an Ethics Framework was in part prompted by receiving this directive, and it is likely that the same is true of the other centres. This implies that a directive from governing bodies, like the one from Ontario Health, can be instrumental in signalling the existence and importance of the ethical dimensions of a problem like the surgical backlogs, and in prompting institutions to respond with materials that explicitly address this. This is important because operative resource allocation and surgical prioritization are typically considered to be administrative tasks (Kelly et al., 2022), rather than framed as ethically or value laden activities.

A Hidden Value: Urgency-First Prioritization

We noted above that several responses to our inquiry focused on classifying urgency in surgical prioritization, and that prioritization is done primarily based on urgency. Importantly, this is an expression of an ethical value in prioritization, even if not articulated as such due to it being status quo. Prioritizing cases that are more urgent over those that are less is a version of prioritizing according to the ‘worst off,’ or ‘sickest-first’ principle (Persad et al., 2009). While this is the status quo in many contexts (e.g., in emergency departments), and well justified from many perspectives, it is crucial to appreciate that this is a resource allocation and prioritization decision, not a foregone conclusion. Explicit ethical attention here also reveals that while ranking levels of urgency is necessary for effective and ethical prioritization, a sole focus on urgency is insufficient to attend to the broader range of clinically and ethically relevant considerations.

To the former, metrics for urgency, such as the P-CATS, do not capture the more fine-grained clinical dimensions of resource allocation and prioritization because they do not provide guidance for allocating between competing levels of urgency between different surgical subdivisions, and they do not provide guidance for prioritizing among cases that are medically similar, or equally ‘urgent’ within the same division. To the latter, focusing on urgency as the beginning and end of relevant considerations when prioritizing surgery obfuscates the costs to ‘elective’ patients who sit on the waitlist in perpetuity. While the patients in these cases are not at imminent risk of losing life or limb, ‘elective’ does not mean surgery is optional, and the quality-of-life costs to these patients and their families are significant.

Importantly, in a context of protracted resource scarcity, urgency seems to become not just the primary factor for prioritization, but the only one. The current context of resource constraint poses a barrier to thinking about prioritization from any lens other than urgency. Urgent cases that enter the system are done soon after, and the same is not true for elective patients. One of the benefits of focusing explicitly on the ethical dimensions of surgical prioritization is that it brings the following reality into sharp focus: until resource constraint is less severe, it is immensely difficult to actually operationalize other ethical values that are considered important in these domains, like equity and beneficence.

For example, considerations of equity could make a difference in prioritizing elective surgery in the following way. When deciding who to prioritize amongst patients who are in the same P-CATS category (i.e., they are ‘medically equal’), with the appropriate data collection, those whose health state has been further undermined by the social determinants of health (i.e., access to care, socioeconomic deprivation), could be granted additional priority on that basis. This approach is similar to the ‘equity-adjustor’ mentioned above in the New Zealand context – a surgical prioritization corrollary for equity-promoting triage protocols (Lo & White, 2021). In giving priority for an explicitly wider group of people, health equity is promoted because the impacts of health inequity has been taken into account. However, implementing an approach like this in how elective surgeries are prioritized can’t make that difference when all that can be done consistently are urgent cases, and where we don’t have enough surgical capacity to work through elective caseloads in a reasonable time frame. This is by way of saying that explicit attention to the ethical dimensions of these issues can also help to clarify the circumstances in which we find ourselves: that when resources are scarce, urgency takes priority, often to the exclusion of fulfilling other stated ethical obligations.

CONCLUSION

When elective surgeries were cancelled during the initial waves of the COVID-19 pandemic, subsequent ramp-ups of operative capacity occasioned an opportunity to see surgical resource allocation and prioritization for what they really are: value laden endeavour that warrant sustained attention, ethical attention included. Attention has understandably turned to clearing the backlog – which continues to grow – as effectively as possible. While this is crucial, these decisions are value laden, and warrant explicit ethical attention. We surveyed whether other provincial centres had developed ethics related materials in relation to the surgical context and presented our findings here. The hope with this analysis is to initiate and encourage ethical dialogue in these domains. Addressing the surgical waitlist is complex and multidimensional, and explicit ethical attention must be part of ongoing solutions. Taking an explicitly ethical lens can help to clarify which values currently do guide resource allocation and prioritization, prompt further discussion on which values should guide resource allocation and prioritization and offer an opportunity to engage relevant parties to work towards consensus on these matters. As institutions become clearer on their normative goals, we can ideally work towards a more equitable, transparent, and grounded provision of surgical care for our paediatric population as we fight the backlog.

TABLES

Table 1: Procedural Principles

Table 2: Substantive Principles

REFERENCES

Arulanandam, B., Dorai, M., Li, P., Poenaru, D. (2021). The burden of waiting : wait time for paediatric surgical procedures in Quebec and compliance with national benchmarks. Canadian Journal of Surgery. 64(1). E14-E22. doi: 10.1503/cjs.020619

Caplan, A. L., Teagarden, R. J., Kaerns, L., Bateman-House, A. S., Edith, M., Arawi, T., Upshur, R., Singh, I., Rozynska, J., Cwik, V., Gardner, S. L. (2018). Fair, just and compassionate: A pilot for making allocation decisions for patients requesting experimental drugs outside of clinical trials. Journal of Medical Ethics. 44(11), 761-767. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2016-103917

Conference Board of Canada Report. (2023). No Child Elects to Wait. https://www.conferenceboard.ca/product/no-child-elects-to-wait-timely-access-to-pediatric-spinal-surgery/

Dossa, F., Zeltzer, D., Sutradhar, R., Simpson, A., Baxter. N. (2022). Sex Differences in the Pattern of Patient Referrals to Male and Female Surgeons. JAMA Surgery. 157(2):95-103. Doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2021.5784.

Downar, J., Smith, M. J., Godkin, D., Frolic, A., Bean, S., Bensimon, C., Bernard, C., Huska, M., Kekewich, M., Ondrusek, N., Upshur, R., Zlotnik-Shaul, R, Gisbon, J. (2022). A framework for critical care triage during a major surge in critical illness. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia, 69(6). 774-781. doi: 10.1007/s12630-022-02231-2

Faa, M. (2023 June 23). Health professionals defend surgery waitlist tool that prioritises Māori and Pasifika people in New Zealand. ABC News. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2023-06-24/m%C4%81ori-pasifika-people-priortised-on-surgery-waitlist-new-zealand/102510010

Garrett, J. R., McNolty, L., Wolfe, I. D., Lantos, J. D. (2020). Our Next Pandemic Ethics Challenge? Allocating ‘Normal’ Health Care Services. The Hastings Center. doi: 10.1002/hast.1145

Glauser, W., (2020). Surgery Backlog Crisis Looming. CMAJ, 192:E593-4. doi. 10.1503/cmaj.1095870

Govind Persad, G., Alan Wertheimer, A., Ezekiel J Emanuel. E.J. (2009). Principles for Allocation of Scarce Medical Interventions. The Lancet. 373(9661). 423-432. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60137-9.

Harris, J. (1987). QALYfying the Value of Life. Journal of Medical Eethics. 13(3). 117-123. doi: 10.1136/jme.13.3.117

Jain, A., Dai, T., Bible, K., Myers, C. (2020 August 10). Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2020/08/covid-19-created-an-elective-surgery-backlog-how-can-hospitals-get-back-on-track

Kelly, P.D., Fanning, J.B., Drolet, B. (2022). Operating Room Time as a Limited Resource: Ethical Considerations for Allocation. Journal of Medical Ethics. 48. 14-18. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/medethics-2020-106519

Lindsay, B., & Barak, C. (2023 April 6). Centralized surgery queues cut patient wait times but surgeons slow to get on board, doctors say. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/health/centralized-surgery-wait-lists-1.6802550

Ogilvie, M. (2022 May 26). Thousands of Kids Waiting Months Too Long for Surgeries in Ontario, Risking Long-term Damage. The Toronto Star. https://www.thestar.com/news/gta/thousands-of-kids-waiting-months-too-long-for-surgeries-in-ontario-risking-long-term-damage/article_f6319a99-ec36-5c6f-977d-5746f8553b90.html

Ogilvie, M. (2023 Oct 26). Childhood on the Waiting List. The Toronto Star. https://www.thestar.com/interactives/she-needed-life-changing-surgery-on-her-leg-but-waited-months-then-years/article_caaa2a8a-685a-11ee-8544-93bc1c3513a8.html

Ontario Health. (2020 June 15). A Measured Approach to Planning for Surgeries and Procedures During the COVID-19 Pandemic. https://www.ontariohealth.ca/sites/ontariohealth/files/2020-05/A%20Measured%20Approach%20to%20Planning%20for%20Surgeries%20and%20Procedures%20During%20the%20COVID-19%20Pandemic.pdf

Ontario Health Newsroom. (2023 Jan 16). Ontario Reducing Wait Times for Surgeries and Procedures. https://news.ontario.ca/en/release/1002641/ontario-reducing-wait-times-for-surgeries-and-procedures

Rahimi, S. A., Dexter, F., Gu, X. (2018). Prioritization of individual surgeons’ patients waiting for elective procedures: A Systematic Review and Further Directions. Perioperative Care and Operating Room Management.10. 14-17. doi: 10.1016/j.pcorm.2017.12.002

Ronald, M., MacCormick, A. D., Koea, J. (2023). Inclusion of ethnicity in surgical waitlist prioritization in Aotearoa New Zealand is appropriate and required. ANS Journal of Surgery, 93: 2567-2568. doi: 10.1111/ans.18699

Vardit Ravitsky. (2022). IAB Presidential Address: Bioethics, justice, and lessons from a global pandemic. Bioethics. 36(5): 482-485. doi: 10.1111/bioe.13037

Shapiro J., Axelrod, C., Levy, B. B., Shriharan, A., Bhattacharyya, O. K., Urbach, D. R., (2022). Perceptions of Ontario health systems leaders on single-entry models for managing the COVID-19 elective surgery backlog: an interpretive descriptive study. CMAJ Open. 10(3). E789-E797. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20210234

Skarsgard, E. (2020). Prioritizing specialized children’s surgery in Canada During the COVID-19 Pandemic. CMAJ, 192:E1212-1213. Doi: 10.1503/cmaj.201577.

Szynkaruk, M., Stephens, D., Borschel, G., James Wright, J. (2014). Socioeconomic Status and Wait Times for Paediatric Surgery in Canada. Pediatrics. 234(2). doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-3518

Truog, R. D., Mitchell, C., and Daley, G. Q. (2020). The Toughest Triage – Allocating Ventilators in a Pandemic. New England Journal of Medicine. 382(21). 1973-1975. doi: 10.1056/nejmp2005689

Urbach D., & Martin, D. (2020). Confronting the COVID-19 Crisis: Time for Transformational Change. CMAJ. 192(21) :E585-6. doi: https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.200791

Valiani, S., Terrell, L., Gebhardt, C., Prokopchuk-Gauk, O., Isinger, M., (2020). Development of a framework for critical care resource allocation for the COVID-19 pandemic in Saskatchewan. CMAJ. 192:E1067-73. Doi: 10.1503/cmaj.200756

Weeks, C., (2023 Sept 25). Children Across Canada Continue to Wait Months or Longer for Surgeries, Report Finds. The Globe and Mail. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-pediatric-surgery-wait-times/.

Wiebe, K., Kelley. S., Kirsch, R., (2022). Revisiting the concept of urgency in surgical prioritization and addressing backlogs in elective surgery provision. CMAJ. 194(29), E1037-1039. doi.10.1503/cmaj.220420

Wiebe et al., (2023). Operationalizing Equity in Surgical Prioritization. Canadian Journal of Bioethics, 6(2), 11-19. doi: 10.7202/1101124ar

Wright J.G., Li K., Seguin, C., Booth, M., Fitzgerald, P., Jones, S., Leitch, K.K., Willis, B. (2011). Development of paediatric wait time access targets. Canadian Journal of Surgery. 54(2). 107-10. doi: 10.1503/cjs.048409